A DIY Guide – The Secret’s Behind the Perfect Hole Saw Technique. Sharpen a hole saw

A DIY Guide – The Secret’s Behind the Perfect Hole Saw Technique

A workman’s staple, the hole saw is a tool you’ll encounter as you start to flex your DIY muscles and branch out into more interesting challenges. They’re used to cut perfectly round holes in a variety of materials. Wood and plaster are common workpieces, but metal, glass, ceramic, concrete, and stone still fall to the hole saw.

Despite the name, this tool looks more akin to a drill bit than a saw – in fact, its cutting edge rests at the end of a large diameter cylinder, and this is spun on a power drill to cut through your chosen material.

Where might you use a hole saw? Here are just a few ideas:

- Installing hardware (such as dead bolts or locks) on doors

- Cutting holes in ceilings to accommodate light fixtures or fittings

- Cutting holes to accommodate drainage or waste pipes

- Making extra connections in pre-existing pipework

- Cutting vents in masonry

- Cutting holes for cables and wires

That list is far from comprehensive, but it illustrates the tool’s diverse array of applications. Learning to use a hole saw is undeniably useful, so let’s get into:

- What a hole saw is

- Why you should use one

- The types available and how to choose the right one

- How to attach hole saw to drill

- How to operate your hole saw

- How to care for your hole saw

- How to keep yourself safe

All in all, you’ll find yourself fluent in hole saw by the time you finish reading this post.

What is a Hole Saw?

Also known as a hole cutter, and sometimes spelled ‘holesaw’, the hole saw is easy to understand but deceptively tricky to master. Let’s start by covering what it is, how it works, why you’d use one, and what components it’s made from.

The hole saw is a large diameter, hollow drill bit with a keen cutting blade along the outer edge. Attach one to a power drill and it rotates at high speed, cutting precise holes into anything from bathroom basins to external walls. The depth of cut is limited by the hole saw’s cup-like shape, but a variety of bit types are available to work around varying requirements.

Metal Cylinder

The body of a hole saw is a wide diameter metal cylinder. Regardless of your cutting edge, steel is standard across the lion’s share of industries. The cylinder is mounted on an arbour, and you’ll notice slots cut into its walls to facilitate the ejection of chips and dust for smooth performance and to prevent stuck blades. Slot number varies between makes and models – 6 is generally the upper limit since more would compromise the hole saw’s strength, and we wouldn’t want that.

Here’s where things get interesting. The metal cylinder of each hole saw culminates with an edge that uses either serrated saw teeth, gulleted/square teeth, or ultra-hard embedded materials to cut through your workpiece.

- Serrated Saw Teeth: Typically set at a 60° angle to allow a penetrating bite into the material being cut, saw teeth are far and away the most common cutting edge. Use saw tooth hole saws for wood, plaster, softer metals, and plastic.

- Gulleted/Square Teeth: Teeth are wider set since raw power is preferred over fine cuts. You’ll use gulleted or square tooth hole saws with more abrasive surfaces, including concrete, brickwork, ceramic tiles, glass, and stone.

- Coated: No teeth are used at all. Instead an ultra-hard material, usually tungsten carbide or diamond, coats the cutting edge. of a niche tool, you’ll use coated hole saws to cut through heavy-duty metals, ceramics, and concrete. Unless you’re a professional, you’re unlikely to encounter the need.

You’ll also want to pay attention to the pitch of teeth and their TPI (Teeth Per Inch) rating, so let’s break down the impact of each factor.

Pitch

Pitch refers to the distance between the point of two teeth (serrated) or the middle of two teeth’s gullets (gulleted/square). A variable pitch hole saw varies that distance, while a constant pitch hole saw maintains the same distance.

- A variable pitch breaks the sawing rhythm; that might sound like a bad thing, but it inhibits vibration for a smoother cut, reduced blade wear, and lower noise levels. Chips and dust eject easily to reduce the chance of clogging or overheating.

- A constant pitch works slower but produces a much finer cut.

TPI

Understand TPI as a measure of tooth frequency along the blade. For example, 18 TPI means 18 teeth per inch, so that tooth frequency is higher than that of a 16 TPI hole saw. TPI numbers vary, but they stay within the general ballpark of 20 to 2.

- Blades with a higher TPI will cut slowly, but, less likely to tear at the fibres of your material, they also cut smoothly.

- Blades with a lower TPI cut faster, but they do tend to tear at fibres to produce a more ragged edge.

Arbor

The arbor isn’t specific to the hole saw, but it’s a vital part nonetheless. It’s the type of tool bit used to grip other moving tool components, essentially the connecting part between your hole saw and your power drill. Most, but not all, hole saws are supplied with an arbor – you’ll occasionally need to purchase your own, so pay attention when you buy.

As you’re browsing, you might consider seeking an arbor with a spring placed over the drill bit. These are known as ejector springs – they contract as you drill and then eject the slug (the cut segment) after the hole has been made.

Arbors can be broken down into fixed or detachable and small or large.

- Fixed Arbors: Said to have an ‘integral shank’, fixed arbors come attached to the hole saw blade. Using one means skipping any dismantling when you need to change saw size.

- Detachable Arbors: Unfixed to the hole saw, detachable arbors can be used with a variety of blades. Using one means skipping the need to purchase again for every hole.

Size comes down to the diameter across the flats of an arbor’s hexagonal shank – so, the distance between one flat face to the opposite flat face.

Reducing the Volume of Shavings for Storage, Transportation, Etc

- Small Arbors: Have a shank size of 1/3-inch (8.75mm) and are used alongside hole saws with diameters between 14mm – 30mm (1/2 – 1 inch).

- Large Arbors: Have a shank size of 7/16 inch (11.1mm) and are used alongside hole saws with diameters between 32mm – 210mm (1 – 8 inches).

Hole saw sets often provide an arbor adaptor. This straightforward threaded attachment fits over your drill bit and onto the collar threads of a large arbor, allowing users to attach a smaller hole saw to the adaptor’s threads.

Drill Bit

You’ll find a drill bit at the centre of each hole saw. Their function is to create a pilot hole, anchoring the hole saw in place to decrease any ‘wandering’ as the cut is made. At the other end of the drill bit is a blunt hexagonal shank that is inserted into and gripped by your power drill’s chuck.

Why Use a Hole Saw?

Let’s take a breath before diving into the particulars of using a hole saw to consider why exactly you’d want to. Other tools can cut holes, so what makes a hole saw the go-to among professionals?

- Leaves the Core Intact: A hole saw works without needing to cut up the core of your workpiece, a notable advantage over twist drills or spade drills, especially when dealing with larger holes.

- Reduced Friction: The walls of the hole saw cylinder are relatively thin, cutting through material with less friction than solid drill bits. Less power is needed, so less strain is placed on your drill and cutting time is drastically reduced. Expect to save on energy, battery life, and time.

- Versatility: A hole saw achieves a greater variation of hole sizes than rival tools – they are particularly valued for cutting large diameter holes.

Types of Hole Saws

We’ve covered how the individual components of a hole saw can differ, but more important is the variation between hole saw types. There are plenty from which to choose, and your decision should be based around:

Keep those points in mind as you peruse our quick overview of common hole saw types:

- Carbon Steel: Your basic general-purpose hole saw performs admirably for the DIY expert or enterprising home-improver. Though not the most durable, carbon steel hole saws are ideal for use with softer materials, including wood, non-laminated plastic, and plasterboard.

- Variable Pitch Bi-Metallic: Bi-metal construction boosts safety by eliminating the chance of shattering, so consider these a good step-up for dealing with slightly tougher materials or working for longer periods. Many boast hardened teeth of high speed steel for faster cutting, and variability lets you cut at different speeds according to your chosen material. Best suited to hardwood, plywood, non-laminated plastic, plasterboard, and non-ferrous metals (such as aluminium, zinc, and copper).

- Deep Cut Variable Pitch Bi-Metallic: Not named through coincidence, the deep cut variable pitch bi-metallic hole saw drill will boast a cut depth up to 42.5mm. Otherwise, it retains the characteristics and benefits of the standard bi-metallic.

- Constant Pitch Smooth Cut: The constant pitch smooth cut hole saw utilizes high speed steel with a tough alloy body. Hardened, abrasion-resistant, and heat-resistant, they’re made for cutting stainless, tool, and mild steel. Plasterboard, wood, and thin plastics also work well. Something to note, the hexagonal shank will sport a slight indentation. Nothing to worry about – it just helps lock the shank into place.

- Tungsten Carbide Tipped: Tungsten carbide tipped teeth deliver fast cutting action and outstanding durability, ideal for those who expect to use their hole saw frequently and for extended periods. Often used as the construction industry’s multi-purpose option, they cut through all woods, plastics, tiles, and metals. Perhaps not quite necessary for personal use, but undeniably nice to have.

- Welded Shank Soffit Cutter: A non-detachable arbor is welded to the base plate, and the saw is made from high speed steel with a variable tooth pitch. A wide diameter makes them seem tailormade for cutting vent holes in soffit boards, and they work well with plywood, metal, and PVC.

- Diamond-Edged: Showcasing a conspicuous absence of teeth, such hole saws are either coated or infused with diamonds. The hardness and durability is exceptional, so high heat and constant resistance are no obstacle. You’ll generally use them to drill through ceramic tiles. Though heat resistant, you should periodically cool them in water.

- Multi Hole Saw: Designed to be used for cutting a range of different diameter holes, the multi-hole is notoriously undiscerning when it comes to material. Wood, non-laminated plastics, plasterboard, chipboard, plywood, and non-ferrous metal (except stainless steel) can all be cut through.

Finally, two separate configurations allow for on-the-fly adjustability:

- Adjustable: Adjustable hole saws allow multiple sizes of holes to be made with the same machine. Portability is improved since everything is contained within a single unit, and you’ll be able to work with various materials without changing up.

- Circle Cutter: One, two, or three adjustable teeth sit on a platform with the pilot bit. Adjusting them allows users to cut holes of almost any size, even beyond a foot in diameter. Superbly flexible, but they’re quite tricky to use.

How to attach a hole saw to a drill

Hole saws pose potential danger, so knowing when and how to use them is key. Whether you’re cutting through wood or dealing with ceramic, you’ll start by properly attaching the hole saw to the drill.

- Determine Necessary Size: Firstly, check your requirements and set the appropriate size hole saw. Cutting through metal? Make sure there’s a bottle of cutting oil or lubricant close at hand before starting.

- Select Your Arbor: If using a detachable arbor, determine the correct one for your hole saw to fit into. At the same time, ensure you have an arbor that will fit your power drill’s chuck.

- Fit Arbor: Now your arbor is selected, insert it through the back of the hole saw.

- Screw Hole Saw and ArborTogether: Screw the hole saw onto the arbor thread, not stopping until it feels as tight as possible. If adjustable, the arbor should protrude past the teeth by around 3/8 inch and then tighten using the set screw.

- Tighten the Hole Saw: Insert the end of your arbor into the drill chuck. 18 volts is the minimum requirement – anything less won’t produce the necessary torque for proper cutting.

- Tighten Chuck: Screw the arbor in firmly until it is securely held by the chuck.

How to Use a Hole Saw Perfectly

Hole saws seem misleadingly easy to use. It’s no mere matter of choosing a spot before pressing down with your drill, and practice must make perfect until you’re confident. During your first few attempts, try using a practice workpiece.

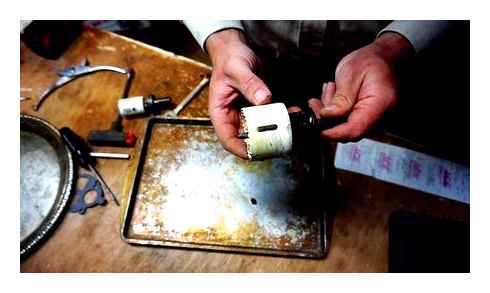

How to sharpen your hole saw and save money Hack/Tip

- Drill Your Pilot Hole: Used to guide the saw, this goes right at the centre of the hole you wish to cut. As you drill, keep the bit level. If your workpiece is freestanding, take the time to secure it to prevent any spinning or other movement.

- Align Drill Bit: Pilot hole made, it’s time to align your arbor’s drill bit within. Check the hole saw’s teeth are all in even contact with the workpiece. If cutting metal, drip a little cutting oil or other lubricant over the blade before starting.

- Keep it Steady: You’ll want to start slow, holding the grill tightly and squeezing the trigger lightly. Only a moderate amount of pressure is needed to push the saw through – instead of forcing it, FOCUS on keeping the saw level.

- Eject Dust and Chippings: Take regular pauses so you can back the drill out from the hole and clear it of dust and chippings. Doing so helps avoid clogging and overheating.

- Saw from the Other Side: To make the final hole smoother, finish your cut from the opposite side, if possible.

- Remove Slug: The slug is just an easy term for the waste material that collects in your hole saw. If you have an ejector spring arbor, it should pop right out – otherwise, dig it out manually.

That covers the basics, but what if you need to drill holes deeper than your hole saw allows or widen an existing hole?

Here’s how to cope with both situations, starting with deep drilling.

- Cut to Depth: As detailed above, use your hole saw to achieve the maximum depth possible.

- Use YourChisel: Grab a chisel and start cutting out as much wood as you can. This should let you go a little deeper.

- Continue Cutting: Once the wood has been cleared, realign your saw and continue until you reach the required depth or make a through-hole.

- Use an Arbor Extension: For added depth, consider buying and attaching an arbor extension. These are long metal rods with a socket on the end to accept the shank from your arbor, and you can use one to reach deeper into holes than conventionally possible.

As for enlarging existing holes, here’s how you play it:

- Clamp Some Scrap: Take some scrap wood and clamp it to your workpiece to provide a solid point on which to secure your drill bit.

- Mark the Centre: One of the problems with enlarging holes is the lack of a pilot hole. Mark the centre of the existing hole on the other side as you clamp your piece of scrap wood.

- Cut: With scrap wood securely clamped and marked, drill a fresh pilot hole into it and then continue as normal.

How to Care for Your Hole Saw

Knowing how to use your hole saw is one thing, but don’t forgo proper care. Here’s the low-down on cleaning, sharpening, and storing.

Cleaning

Regular cleaning extends the life of what can be a very expensive tool. After each use, clean your hole saw thoroughly to rid it of any dust or chippings. Left to their own devices, such detritus can become stuck or else damage the teeth – it’s worth keeping in mind that they’re very tough to sharpen once dulled.

It also helps to back the saw out occasionally while cutting to remove waste material and keep the blade cool. Apply even pressure as you cut to avoid tooth strippage.

Sharpening

If your hole saw should become dulled, the relatively low cost of replacing the blade should be enough to dissuade you from sharpening. If you’re set on sharpening, you can use a hand file on each individual tooth, though a hand-held electric grinder will slightly cut down on elbow grease. A bench grinder also does the job, but extensive time and concentration is required – honestly, it’s largely advantageous to replace instead of re-sharpen.

Storing

Finished with your latest project? Take a few minutes to see your hole saw properly stored if you want it ready to go next time round. It’s not too hard – simply store your hole saws in a dry place where they won’t be knocked about or corroded by the elements.

Safety Equipment When Using a Hole Saw

The chance of injury falls significantly when you don the right safety wear and employ the proper safety equipment. Hole saws don’t require much, but what they do require is vital.

- Eye Protection and Mouth Guard: To prevent dust or splinters getting in your eyes or being inhaled.

- Safety Gloves: To maintain proper purchase through cutting.

- Ear Protection: To safeguard your hearing while drilling for extended periods.

If working with any material save wood or cast iron, cutting oil or lubricant must be used to reduce resistance and extend the saw’s life. When using a more powerful drill to cut through a tougher material, the machine may experience ‘kick back’; under such conditions, you’re well advised to use a drill with a side-handle to afford additional stability and control.

Don’t toss those spade bits quite yet! These three sharpening methods can help you get more use out of your old spade bits.

We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs.

Spade bits, it seems, are always encountering nails, at least in the kinds of rough drilling chores that renovation work involves. Even if you’re well-versed in how to use a drill, nails, screws, staples, and other blade-dulling obstructions happen. Luckily, spade bits are among the easiest of drill bit types to sharpen.

The Anatomy of a Spade Bit

Before we get around to sharpening, let’s take a look at the anatomy of a spade bit. There are five main parts, three of which you’ll sharpen:

- The shank is the part of the spade bit that inserts in the drill’s chuck. You’ll want to clamp this part into a vise while you’re sharpening the bit.

- The cable hole is for attaching electrical cable, allowing users to pull the wire back through the hole after drilling.

- The center point is the tallest point on the business end of the spade bit, and it holds the bit’s location as it drills. It will need sharpening.

- The spurs are the spiky wings at each end of the spade bit, and they do much of the initial cutting, determining the width of the hole. They also need sharpening.

- The flats are the beveled sections between the spurs and the center point, and they remove the bulk of the material. They need to be sharpened as well.

How to Sharpen a Spade Bit

If you don’t know which parts of the bit to sharpen, or why, you might struggle with the process. The following sections will point out which areas to FOCUS on so you’ll know how to sharpen a spade bit.

STEP 1: Sharpen the flats.

The flats do the bulk of material removal, and they need to be sharp to work effectively. As the bit spins around the center point, the flats come in contact with the wood inside the cutting diameter. If the flats are sharp, they’ll shave off a little bit more with every rotation. If they aren’t, they’ll heat up and eventually burn the wood.

STEP 2: Sharpen the center point.

The center point doesn’t remove much material, but it’s vital for drilling an accurate and symmetrical hole. The point bores into the wood ahead of the spurs and flats, so it needs to be sharp to stay on course. If it’s not sharp, making progress will be difficult and you may not end up with a symmetrical hole.

STEP 3: Sharpen the spurs.

The spurs align with the edge of the spade bit, and it’s important that they’re sharp to make drilling easier and accurate. If sharpened carefully, these points will efficiently remove the outer material, leaving a perfectly sized hole for the rest of the spade bit to pass through. If they’re dull or sharpened incorrectly, the user will have to force the bit through, sacrificing accuracy.

Note: Not all spade bits have spurs. Some have flats that extend from the center point to the edge of the bit. These bits are easier to sharpen, but they’re a bit less accurate.

Methods for Sharpening a Spade Bit

There’s more than one way to sharpen a spade bit. The following guides offer three methods, each with its pros and cons. Be sure to choose the method that sounds most applicable to your situation. It helps if you already own the required materials.

Use a bench grinder.

Set the tool rest on your bench grinder 8 degrees down from horizontal (that is to say, 8 degrees past 3 o’clock, when looking at the end of the grinding wheel).

Position the bit with one of its shoulders flush to the wheel with the bevelled side visible from the top. Before starting the grinder, tighten a stop collar on the shaft of the drill just a hair from the edge of the tool rest. Now, start the machine and grind the edge until the stop collar prevents further grinding; turn the bit over, line up the cutting flat on the opposite shoulder, and repeat. The stop collar will ensure that the bit is ground symmetrically. Be careful not to grind the center point during sharpening, which could throw its symmetry off-center.

Keep in mind that this method will produce a sharp flat, but it doesn’t do much for the point. It will also remove the spurs entirely, so it’s best for bits without them. But, as long as the flats are sharp, it should add usable life to the spade bit.

Use a file.

While a bit more tedious and time-consuming, sharpening a spade bit with a file is far more accurate than using a grinder and it leaves the bit entirely intact (aside from removing the dulled metal). All you need is a vise or clamp and a set of needle files (which you can find on Amazon).

Start by clamping the spade bit into a bench vise or clamping it firmly to a work table. Then, choose the appropriately sized metal file for the flats. Match the file’s angle to the angle of the bevel on one of the flats (this is easier than it sounds). Make a few forward passes, applying light pressure and counting as you go. Once the flat is sharpened, switch to the other side of the spade bit, and make the same number of passes on that side to ensure symmetry.

The same process applies to each spur and the center point. Simply match the angle of the bevel and make a few forward passes with the file, repeating the process on the other side.

Note: Your file should go past the bit from shank to tip, not tip to shank. If you file toward the bit, you will risk running your hand into the center point or spur, causing a potentially serious injury.

Use a drill sharpening machine.

If you’re lucky enough to own a drill sharpening machine with a spade bit attachment, you can use it to freshen up your dull spade bits. The process is fairly easy:

- Clamp the spade bit into the spade bit holder. This is a separate attachment from the twist bit holder, and your machine may not have one. If that’s the case, use one of the previous methods to sharpen your bits.

- Insert the spade bit holder into the machine and slide the grinding wheel to the left of the bit. Lock the bit into place with the lever on the spade bit holder. The holder will act as a jig during sharpening.

- Slide the spade bit holder back and turn the sharpener on. Slide the holder forward so the bit makes contact with the grinding wheel, and use the lever or squeeze handle to move the grinding wheel left and right. Be careful not to grind the spurs off, if the bit has them. The shape of the grinding wheel allows it to refresh their edges as well as the edges on the center point.

- Remove the spade bit holder from the sharpening port, flip it over, and repeat the sharpening process.

Testing a Freshly Sharpened Spade Bit

The best way to test a freshly sharpened spade bit is to drill a few holes in a piece of scrap wood. Be sure that the wood doesn’t contain nails, screws, or staples, or else you’ll have to go back to the drawing board.

As the bit bores into the wood, it should cut smoothly without much hopping or wobbling. It also should not generate smoke. Stop about halfway through the hole and check for any burning. If the bit is cutting smoothly and not causing any burning, and if the hole looks symmetrical, you’ve sharpened it properly and it’s ready for use.

FAQs About How to Sharpen Spade Bits

If you are still confused about using and sharpening spade bits, here’s are some of the most frequently asked questions on the topic.

Q. What projects are spade bits designed for?

Spade bits are popular for rough carpentry and electrical projects because they enable users to bore holes quickly and accurately in wood, plywood, and other softer materials. They’re also helpful for installing doorknobs in slab doors if used carefully.

Q. Can a spade bit be used in a drill press?

You can use a spade bit in a drill press, but there are a few things to keep in mind if you do:

- Ensure that the table is low enough that the bit won’t strike it. You can add a sacrificial piece of wood underneath, if necessary.

- Be sure that the wood is firmly clamped to the drill press. Spade bits have a tendency to grab wood, potentially whipping it across the table like a baseball bat.

Q. Is a spade bit different from a Forstner bit?

Yes. A spade bit’s design makes it useful for drilling entirely through a material. A Forstner bit can drill through a material, but it’s commonly used for creating round, flat-bottomed recesses in a workpiece to accommodate dowels and hinges that don’t pass completely through.

Q. When should a spade bit be used and when should a hole saw be used?

Spade bits are rough carpentry and electrical tools, so they’re best used to bore holes no one will see. Hole saws are more appropriate for applications where the appearance of the hole and surrounding materials matter, such as:

Also, spade bits are not for use with metal, while some hole saws are designed specifically for this purpose.

Final Thoughts

We hope you now know that the pile of dull spade bits in your workshop isn’t destined for the garbage and that these bits actually aren’t difficult to sharpen. Whether you choose to use a bench grinder, a needle file, or that old drill bit sharpener, those old bits can be brought back to life.

How Can I Sharpen My Carbide Saw Blade?2020/08/28

If treated properly modern carbide blades will provide you with a long life of clean, chip-free, precision cutting. However, at some point in time, every blade will become damaged or dull and need to be replaced. Here are some of the most common indicators that a blade needs replacing.

The blade starts chipping or splintering your work 2. You can smell wood burning, see smoke while cutting and see burn marks on the cut edge 3. The saw seems to be cutting slower and sticks in the cut 4. The blade will not produce a clean, straight cut 5. You notice chipped or missing teeth 6. Your blade has a heavy buildup of pitch or other material on the blade and around the teeth 7. The blade wobbles and will not cut straight, indicating it is warped.

The key to maintaining clean, professional cuts and protecting your equipment is knowing when your blade needs to be replaced.

Should I Replace or Resharpen My Blade?

A good quality carbide blade can be sharpened 3-4 times before some or all the teeth need to be replaced and sharpening is a fraction of the cost of purchasing a new blade. As long as your blade is not warped or severely damaged, the correct answer is yes, the blade should be sharpened. However, this is not a do-it-yourself project; carbide blades can only be properly sharpened by professionals, with the equipment and expertise to do the job properly. Improper sharpening will not only change the cutting characteristics of your blade but could destroy it completely. Carbide teeth are so hard, they can only be sharpened using an exceptionally fine grit diamond wheel. Contrary to some information found online, a diamond blade used for cutting ceramic tile is way too coarse for this purpose and will ruin the carbide tip.

The biggest challenge to restoring a blade to its original factory specifications is the grinding or sharpening process. For optimal performance carbide teeth need to be sharpened on all four sides. Each tooth should be ground on the top, face and sides and each tooth has multiple angles that must match and be ground precisely the same. If even one or two teeth are off by as little as 1/1,000“ the blade with not cut properly, if at all. Imagine if two teeth on a 60-tooth blade are slightly larger than the rest, your fine 60 tooth finishing blade has become a very rough-cutting 2 tooth ripper.

The other challenge with merely sharpening the teeth is that your blade has not been cleaned and more importantly checked for flatness. A sharp blade with rust or pitch buildup will not provide optimum performance. It will leave marks on your material, build up heat on the blade and ultimately cause unnecessary wear on equipment. Heat buildup causes warping and if a blade is not checked for flatness all you have is a sharp, warped blade that will not cut straight or clean.

How To Get A New Blade Every Time:

For the past 45 years, Exchange-A-Blade has been producing a wide range of Professional and Industrial quality power tool accessories, with saw blades being the most popular category. When you purchase one of our blades you are guaranteed that you will always be able to exchange it for a completely new blade, which has been remanufactured to the precise specifications of the original.

Each blade goes through a ten-step manufacturing process which is constantly inspected and quality controlled. After being cleaned and buffed, blades are tested for flatness and any chipped or missing teeth are replaced. All blades go through a complete sharpening process, on robotic, computer-controlled sharpening machines. They are sharpened on the face, top and sides and the carbide tips are honed to a mirror-like finish with 400, 650 and 1,000 grit diamond wheels. This means your blade has the best cutting edge, to provide you with optimal performance and long life. Blades are again polished, and rust proofed, before final inspection, laser identification and labelling.

Our remanufacturing process is so sophisticated that it is impossible to tell the difference between one of our brand-new blades and one which has gone through our state-of-the-art remanufacturing process.

As with any Exchange-A-Blade product, you Buy It, Use It, and Exchange It. It doesn’t matter how dull it is or if it has chipped or missing teeth, there is never an extra charge. You will always get the same exchange credit towards the purchase of your new blade. While a carbide blade can only be sharpened 3-4 times before it needs to be replaced, an Exchange-A-Blade blade can be exchanged forever.

Saving Money, Saving Resources, and Saving the Environment:

We are often asked why we have invested so much into our manufacturing and exchange process when it would be so much easier to simply sell it and forget it. For the past 45 years, our Company culture has been one of providing our customers with the best possible products which save them money, save resources and help preserve the environment.

At EAB Tool, every product we sell has an end of life plan. Each blade that is exchanged is carefully inspected and the best are put through our ten-step manufacturing process and returned to new.

Blades that do not meet our strict remanufacturing standards are recycled back into basic steel. Each year EAB Tool recycles over 65 tons of steel which is kept out of our landfills and reduces the resources and energy required to produce new steel.

With Exchange-A-Blade products you are guaranteed the best quality blades, environmentally responsible products and continuous savings with our green exchange system. Find the right blade for your next job.

Wood Boring Drill Bits: Spade Bits, Hole Saws, and Self Feed

We all know that drill bits have their limits when it comes to the size hole you can drill. But what happens when you need to do some larger wood boring?

As a teenager, I decided that I would replace the soft, rotted plywood back deck of our old bass boat. Being relatively ignorant in the ways of tools and working on getting my junior man card, I went to work ripping out the carpet and unscrewing the now very rusty fasteners. Cutting the new board and installing it wasn’t too much of a challenge. The problem came when I needed to reinstall the pedestal seat. It was secured by bolts but also sat several inches down through a 2-1/2 inch hole.

Looking back at trying to cut that #%@! hole… what was I thinking? I started with the largest drill bit I had in the center, then tried to work outward with a hand saw. When that didn’t work, I tried drilling holes in a circle and connecting the dots with that same dull hand saw. I did eventually get it in there, but it took a heck of a lot longer than it needed to and man, was it UGLY!

Had I known what to look for with spade bits, hole saws, and self-feed bits, I might have spent the afternoon fishing instead of cussing and sweating. Fortunately, I’m wiser now, both in my use of tools and the English language. I’m here to pass on that wisdom along with some help from Milwaukee Tool and their accessories.

Wood Boring with Spade Bits

Hole Diameter Range

Spade bits are going to cover the smallest of your wood boring needs. In fact, the smallest spade bits can be in the same range as a standard wood drill bit. Often called flat boring bits (or variations on that), spade bits come in diameters between 1/4″ and 1-1/2″

Characteristics

Spade bits like Milwaukee Flat Boring Bits have a shape that resembles a paddle. A brad point or threaded tip guides the bit into the wood and through the cut. The sharpened edges of the bit take small slices of wood out and eject them out of the hole. Use spade bits in high-speed mode up to 1″ in diameter and sometimes larger, depending on the design. The largest spade bits typically require low-speed mode to deliver the required torque to the bit.

A good, sharp spade bit lets you apply minimal downforce on your drill to make the cut. You can put additional pressure on it to drill faster, but it isn’t necessary. Particularly with larger bits, you’ll want to use your drill’s side handle if it has one. Today’s drills deliver a lot of torque and the bit can bind up causing the drill to twist your wrist or elbow painfully. Some spade bits have a 1/4″ hex shank that you can attach to your impact driver. Spade bits are less expensive than other wood-boring choices.

When to Use Spade Bits

Spade bits like Milwaukee Flat Boring Bits are a great option for cutting holes up to 1″ in wood that doesn’t require a fine finish. The breakthrough with a spade bit can be rather unsightly though. If you’re going to be leaving one side as the finished surface, drill into that side and let the breakthrough happen on the side you can’t see. Once you need to drill holes over an inch (and no longer in high speed with a spade bit), it’s time to look at hole saws.

Wood Boring with Hole Saws

Hole Diameter Range

Hole saws come in three basic designs. You typically use diamond grit hole saws in tile, masonry, and glass applications. Bi-metal works well for metal and often finds its way into wood applications. We find carbide-tipped hole cutters efficient for cutting wood. I’ll FOCUS on those next. You can typically find this style of wood-boring accessory as small as 1-inch. Conversely, they go all the way up to around 6-inches.

Characteristics

The hole saw consists of two parts: a mandrel and the hole saw. Collectively, we usually referr to the whole thing as a hole saw. The mandrel has a threaded and sometimes a locking coupling built around a drill bit that holds the saw in place. The pilot bit guides the cut. Milwaukee’s Big Hawg Hole Cutters actually employ a replaceable spade bit. This reduces the amount of friction against the core to improve the efficiency of the cut.

Because the hole saw as a system is much more complex than a spade bit, they are designed to be able to change hole saws around the same mandrel. This saves money. Hole saws require more torque than spade bits, so the shaft has to be thicker to avoid damage. You’ll need a 1/2″ drill for most hole saw systems.

A hole saw works by shredding away just the circumference of the hole rather than chewing out the entire hole like a spade bit or Forstner bit. This results in a solid core or plug you need to remove from the saw at completion.

Carbide vs Bimetal

Look at the teeth of the hole saw to see the difference between carbide-tipped wood boring and bi-metal general-purpose designs. Wood-boring hole saws have 2, 3, or 4 carbide teeth depending on the diameter. You can actually sharpen these teeth when they get dull over time. To give you an idea of sharpening cycles, Milwaukee Big Hawg Hole Cutters can bore up to 600 holes before needing sharpening. Bi-metal hole saws… well, I wouldn’t sharpen all those teeth. In fact, we recommend you don’t try.

While you can certainly use bi-metal hole saws, they drill up to 10 times slower than carbide-tipped hole saws designed for wood boring. Let the hole saw and drill do the work, and you should be able to drill at high speed most of the time. With larger diameter holes, drop the RPMs (speed) and use that higher drill torque.

When to Use Hole Saws

Hole saws like Milwaukee’s Big Hawg Hole Cutters are perfect for wood boring 1″ – 6″ rough-cut holes. It is possible to get bigger hole saws (Milwaukee Big Hawg goes up to 6-1/4″), but you’re really straining a typical 1/2″ drill at that point and you’ll start needing more specialized equipment.

Like spade bits, hole saws are a rough-cut wood-boring accessory. The breakthrough leaves a rough edge that you need to either sand or cover for finished work. Like spade bits, bore in from the side you intend to use as your finished surface. That hides the breakthrough side from view.

Wood Boring with Self Feed Bits

Hole Diameter Range

Self-feed bits typically handle hole sizes between 1 and 4 5/8-inches. Don’t confuse these with Forstner bits that can start as small as 1/4-inch.

Characteristics

Self-feed bits have outer teeth that cut a circumference like hole saws and a radial blade that slices out the core like a spade bit. The result is a cleaner finish that neither style can accomplish on its own. Self-feed bits also have a threaded tip that pulls the bit through the wood. The threaded tips like those on Milwaukee Switchblade Self Feed Bits stick out further than that of a Forstner bit to act as a guide and pull the bit ahead. They are usually favored by contractors who aren’t concerned with simply creating a recessed hole.

Most self-feed bits are constructed in a way that lets you sharpen the radial blade. Milwaukee Switchblade Self Feed Bits take it one step further. By adding a removable blade edge, the bits offer just as fine a finish while saving you time. The removable blades, like those from Milwaukee, use hardened steel. You still get a lot of life out of them. Just switch them out when they wear down instead of sharpening them.

Like hole saws, self-feed bits require a lot of torque to chew out a hole. You’ll need a 1/2″ drill to accommodate the larger diameter shaft. You’ll also want a spare battery nearby if you’re using a cordless model. Only with the smallest diameters will you be able to drill in high-speed mode with self-feed bits. You’ll make most of your cuts in high torque mode.

When to Use Self Feed Bits

Because self-feed bits fall into a range that is covered by spade bits and hole saws, it can be confusing knowing when to use them. Forstner bits are finish bits that woodworkers and carpenters rely on to make cleaner through holes or recessed holes in wood. Self-feed bits, however, are purely for powering through wood as fast as possible. For applications like under cabinet lighting installations, using a jig and handheld drill are fine with a Forstner bit. When precision is your goal, you’ll find most woodworkers turning to a drill press with a Forstner bit and avoiding that self-feed tip. However, general contractors, remodelers, and plumbers will be looking for the threaded tip found on Milwaukee’s Switchblade Self Feed Bits.