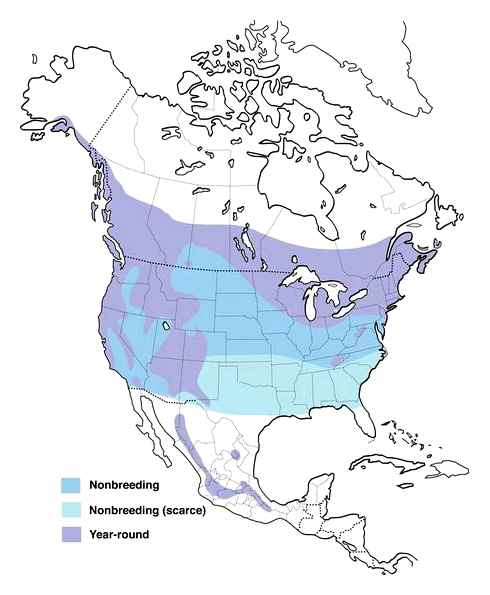

Northern Saw-whet Owl. Saw whet owl range

Northern Saw-whet Owl Information

Habitat: Breeding habitat: A wide variety of woodlands including coniferous, mixed coniferous/deciduous, and deciduous. Prefers coniferous forests. Also, tamarack bogs and cedar groves.

Winter habitat: Similar to breeding habitat but may also include rural towns and suburban areas.

Diet: Mainly small mammals, especially deer mice but also other mice, voles, lemmings, shrews, juvenile squirrels, juvenile chipmunks, and occasionally small birds. Also consumes insects such as grasshoppers and beetles.

Additional Information

Northern Saw-whet Owl Photos, subspecies, description, habitat, food and feeding, breeding, movements and life span. (From Owling.com)

Northern Saw-whet Owl

Northern Saw-whet Owl Identification Tips

New England Range

The Northern Saw-whet Owl is found year round throughout New England.

Northern Saw-whet Owl Range Maps from Cornell

Northern Saw-whet Owl Christmas Bird Count Map

New England is located in the northeastern United States and includes Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont.

Northern Saw-whet Owl

These owls are considered to be some of the smallest owls in North America.

Many Northern Saw-whet Owls move south for the winter, migrating at night, and preferring dark, windless nights in which to move. They roost in dense cover, sometimes in the same place night after night in the winter, though usually in a different place each night during the breeding season.

Northern Saw-whet Owls hunt at night for their primary prey of small mammals. If there are leftovers from the meal, they are stored on a branch for later retrieval in four or five hours. Frozen leftovers are warmed up by sitting over it as though incubating an egg.

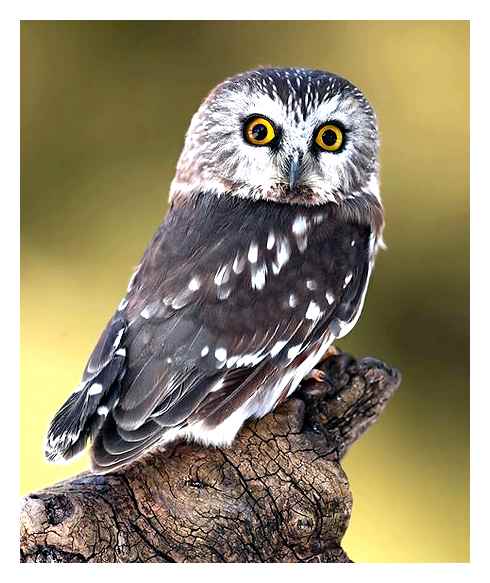

Description of the Northern Saw-whet Owl

BREEDING MALE

The Northern Saw-whet Owl is a small owl with brownish upperparts spotted with white, whitish underparts streaked with brown, and yellow eyes.

Juvenile

Juveniles are dark brown with bright buffy bellies.

Habitat

Northern Saw-whet Owls inhabit coniferous forests.

Diet

Northern Saw-whet Owls primarily eat small mammals.

Behavior

Northern Saw-whet Owls forage primarily at night, watching for prey from a low perch and swooping down to capture it.

Range

Northern Saw-whet Owls are resident in parts of the northeastern and western U.S. and southern Canada, occurring in a somewhat larger area in winter. The population may be declining.

Fun Facts

Northern Saw-whet Owls are well hidden in conifers as they roost by day, making them difficult for birders to find.

Northern Saw-whet Owls often respond to imitations of their song.

Nesting

The Northern Saw-whet Owl’s nest is in a tree cavity, such as an old woodpecker hole.

Number: Usually lay 5-6 eggs. Color: White.

Incubation and fledging: The young hatch at about 27-29 days, and begin to leave the nest in about another 4-5 weeks, though continuing to associate with the adults for some time.

Bent Life History of the Northern Saw-whet Owl

Published by the Smithsonian Institution between the 1920s and the 1950s, the Bent life history series of monographs provide an often colorful description of the birds of North America. Arthur Cleveland Bent was the lead author for the series. The Bent series is a great resource and often includes quotes from early American Ornithologists, including Audubon, Townsend, Wilson, Sutton and many others.

Bent Life History for the Northern Saw-whet Owl – the common name and sub-species reflect the nomenclature in use at the time the description was written.

now Northern Saw-whet Owl – Aegolius acadicus SAW-WHET OWL CRYPTOGLAUX ACADICA ACADICA (Gmelin)HABITS

I shall never forget the thrill I experienced when I first met this lovely little owl. It was in my boyhood days, and I was returning home just as darkness was coming on. As I was leaving the woods, a small, shadowy form flitted out ahead of me and alighted on a small tree within easy gunshot; it flew like a woodcock, but I knew that woodcocks do not perch in trees. I was puzzled, so I put in a light charge and shot it. I was surprised and delighted when I picked it up and admired its exquisite, soft plumage and its big, yellow eyes. I had never seen so small an owl, or one so beautiful. After some research in the public library, I learned its identity, and eventually had it mounted by a boy friend who knew how to “stuff” birds. Many years passed before I ever saw another.

This little owl is widely distributed throughout much of North America, but it is so nocturnal and retiring in its habits that it is seldom seen and is probably much commoner than it is generally supposed to be. Unlike the screech owl and the barred owl, it is seldom heard at night, except for a few weeks during the mating period.

Courtship: We common mortals, who cannot see in the dark, know very little about the courtship performances of the owls, except what we can learn from listening to their springtime voices. All owls are more active and noisy at the approach of the breeding season than at other times, and the saw-whet owl is particularly so. Major Bendire (1892) quotes Dr. William L. Ralph as saying: “Just before and during the mating season these little Owls are quite lively; their peculiar whistle can be heard in almost any suitable wood, and one may by imitating it often decoy them within reach of the hand. Upon one occasion, when my assistant was imitating one, it alighted on the fur cap of a friend that stood near him.” W. Leon Dawson (1923) writes:

During the brief courting season, when alone the notes are heard, the male is a most devoted serenader; and his song consists of breathless repetitions of a single syllable, whoop or kwook, vibrant and penetrating, but neither untender nor unpleasing. In the ardor of midnight under a full moon, this suitor whoops it up at the rate of about three whoops in two seconds, and this pace he maintains with the unfailing regularity of a clock. But to prevent his lady love from going to sleep, he changes the key occasionally. In quality this Nycteline note is not unlike the more delicate utterance of the Pygmy Owl. There can be no confusion, however, as between the incessant cadences of the Saw-whet and the xylophone “song” of Glaucidium.

Nesting: M any years ago Herbert K. Job showed me a nest in an old flicker hole in a dead pine stub in which a saw-whet owl had laid three sets of eggs in a single season. As the owl had popped her head out each time he rapped the stub, I made a point of rapping every likely looking stub I passed thereafter. But it was not until March 19, 1911, that I succeeded in finding another nest of this owl m a very similar situation. I was crossing an extensive clearing, near Taunton, Mass., where a large tract of heavy white-pine timber bad been cut off, when I saw a large stub of a dead white pine that the wood choppers had left as worthless; and there was an old flicker’s hole in it about 18 feet from the ground. I rapped the stub, as usual, and was delighted to see a small, round head appear at the opening; thinking that we were too early for eggs and not wishing to disturb her too much, we came away and left her. I visited the nest again on April 1 and 8, to show the owl to a number of my ornithological friends, and on each occasion the owl appeared at the opening after rapping the tree or starting to climb it; she would not leave then until I almost touched her; she then perched on a small tree within ten feet of a party of 29 people, while I was at the nest. On April 11, when I came to collect the eggs, she sat even more closely; rapping was of no avail until my companion, Chester S. Day, climbed up and looked into the hole; she finally popped her head out within a few inches of his face (p1. 57) but would not leave then until he pulled her out; she then perched for some time on a small sapling nearby, where she disgorged a pellet with considerable effort. The nesting cavity was about 12 inches deep and barely large enough to admit my hand and arm. There were six eggs in the nest, one in the center and the other five around it, partially buried in the fine chips usually found in flickers’ nests, mixed with numerous feathers of the owl. Incubation in the eggs varied from one-quarter to two-thirds.

Dr. Ralph wrote to Major Bendire (1892) as follows:

We found these birds quite common in Oneida County, New York, especially in the northern and eastern parts. Their nests are not very hard to find, and it seems strange that so few have been taken. Those found by Mr. Bagg and myself were all in the deserted holes of Woodpeckers and the eggs were laid on the fine chips found in such burrows without much of an attempt at making a nest. They were all in woods, wholly or in part swampy, such situations being particularly congenial to these birds, who usually frequent them throughout the year.

Saw-whet Owl Chilling By Fan

The first nest was taken near Holland Patent, New York, on April 7, 1886. It was situated 22 feet above the ground in a dead maple stump, and contained seven eggs ranging from fresh to slightly incubated. The second was found near the same place on April 21, 1886, also in a dead stub 40 feet above ground. It contained five young birds and an egg on the point of hatching. The third was found on the same day near Trenton Falls, New York, likewise in a dead stub 20 feet above the ground. It contained seven eggs which were heavily incubated. The fourth was found at Gang Mills, Herkimer County, New York, April 30, 1886, in a dead stump 50 feet above ground, and likewise contained seven eggs on the point of hatching. The fifth and last was taken near Holland Patent, New York, April 30, 1889, and was situated in the dead top of a maple tree 63 feet above the ground, and contained four eggs ranging from fresh to slightly incubated. I believe they lay their eggs at intervals of about two days.

On July 3, 1893, Mr. Gerrit 8. Miller, Jr., and I were setting out a line of traps in a heavy white pine swamp that lies along Red Brook in the town of Wareham, Mass. We noticed a large old pine stump which was broken off about 25 feet above the ground and full of Woodpeckers’ holes, and pounded on it. We had pounded but once or twice when a Saw-whet Owl popped her head out of the uppermost hole and kept it there motionless, although I fired at her three times with my pistol. The third shot killed her and she fell back into the hole.

On taking the bird out, I found there was a nest containing seven eggs. The nest was quite bulky and composed of gray moss (Usnee) interwoven with small pieces of fibrous bark, a few pine needles, small twigs, and feathers of the bird herself. The hole in which the nest was found was 18 feet from the ground and about 8 inches deep.

In the nest besides the eggs was a half eaten red-backed mouse (Evotomys gapperi).

Three of the eggs were in various stages of incubation, one being on the point of hatching,: in fact the young bird had already cracked the shell. Three were addled, and one was perfectly fresh.

George W. Morse writes to me, on the nesting of this owl in Oklahoma: “They are apt to nest 14 to 18 feet up in an elm snag. The nest usually consists of chips of decayed wood, occasionally a few leaves surrounded by a circle of twigs from 6 to 12 inches long. These twigs protruding from the hole are frequently indications of the nest, since the saw-whet is not easily flushed by pounding on the tree, as are other species. When the female leaves, she first drops down and then flies directly up to a limb at the same height opposite the nest, alighting first across the limb, then turning parallel with it, keeping up a bobbing, peering motion of the head and neck in an apparent effort to adjust her eyes to the light and discover the cause of the disturbance.”

Numerous other accounts of the nesting habits of the saw-whet owl have appeared in various publications, but they are all more or less similar. Old deserted nests of woodpeckers seem to be the sites oftenest chosen, with a decided preference for flicker holes, as these are about the right size. I believe that the owls never bring in any nesting material, but lay their eggs on the fine chips usually found in such cavities; the numerous cases reported, where other material has been found in the nesting holes, merely indicate, in my opinion, that flying squirrels, white-footed mice, or other small rodents had built their nests in these holes, and that the owls had not taken the trouble to remove the material. Most observers agree in stating that this owl will usually show itself at the entrance of the hole when the tree is rapped, its little round head completely filling the entrance, and remain there until further disturbed; this is in marked contrast to the behavior of the screech owls under similar circumstances.

There are at least two cases reported of this owl nesting in open nests of crows or herons, but I believe that these are cases of mistaken identity. The normal habit of the saw-whet owl is to nest in deep woods, or swamps, but Ned Hollister (1908) reports a case in Indiana, where “the nesting site was in a lawn shade tree close to the house.~’ William Brewster’s (1881) first set of eggs of this owl was taken from an artificial nest made from a section of a hollow trunk, boarded up at the open ends, with an entrance hole cut in the side, and nailed up in the woods. “No nest was made, the eggs being simply laid on a few leaves which squirrels bad taken in during the winter.”

Lewis Mc. Terrill (1931) says of a nest he found in the Montreal district:

The nesting locality of the Saw-whet Owl was by the bank of a stream draining an upland pine wood and the nest was barely twenty feet from the ground in an old cavity in the decayed top of a basswood stub, in the deep shade of surrounding saplings. It is probable that a Flicker was responsible for the excavation, but the entrance had become enlarged and ragged through decay and bore little semblance to the neatly chiselled nesting place of that bird [p1. 60].

The Owl very considerately appeared at the entrance as I approached and when I reached the cavity it merely flew to a sapling six fcet distant and stared at me without other demonstration while I examined the single fresh egg, resting on chips of rotten wood, ten inches below the opening. Almost as soon as I had descended, the Saw-whet shook its feathers, flew back and disappeared into the cavity, reappearing in a moment to watch my movements. This was the usual procedure during succeeding visits, except that it was sometimes necessary to rap the stub lightly in order to bring the bird to its doorstep. The only note of protest heard in the daytime was an occasional snapping of the mandibles. This was more noticeable after the young were hatched.

Rockwell and Blickensdcrfcr (1921) describe a nest that was in an unusual location in Colorado, quite in contrast with the usual location in deep, shady, damp forests, or near water; they say: “The tree (a large, dead yellow pine) in which this nest was located was on an exposed slope commanding a wide view of the adjacent country. The surrounding timber was sparse; the nesting cavity faced directly south into the bright sunlight and was unshaded except for a single overhanging dead branch; and the immediate surroundings were very dry. The nearest stream was fully half a mile distant and there was not even a trickle of spring water closer at hand.”

Eggs: The saw-whet owl lays four to seven eggs, five or six being the commonest numbers. The eggs are usually oval in shape, but sometimes slightly ovate or more nearly globular. The shell is smooth, with little or no gloss, and the color is pure white. The measurements of 52 eggs average 29.9 by 25 millimeters; the eggs showing the four extremes measure 31.5 by 25.2, 30 by 27, 28.3 by 25.4, and 28.9 by 23.6 millimeters.

Young: Theperiodofincubationhasbeen estimated as from 21 to 28 days; Mr. Terrill (1931) says “at least 26 days and probably longer.” Both sexes are said to assist in this, but probably most of it is done by the female. The eggs are l’aid at intervals of from one to three days, and, as incubation begins with the laying of the first egg, the young hatch at variable intervals, and it sometimes happens that newly hatched and nearly grown young are found in the same nest.

Mr. Terrill says in his notes: “At birth the nestlings were blind and helpless and very tiny, with a scanty covering of whitish down. At the age of 8 to 9 days the eyes were partly opened and the iris was a dark inky color without lustre. When 16 to 17 days old, the upper parts were a dark chocolate-brown. The development of the eyes was very gradual, the yellow iris being first noted at this age, though the yellow coloring was not so bright and clear as at the age of 19 to 21 days, and the lids were never fully opened. At the age of 26 to 28 days one of the owlets could fly about 15 feet from a log, but was apparently unable to rise from the ground. The young left the nest some time bet~veen July 17 and 22, when the oldest was from 27 to 34 days of age and could probably fly fairly well.”

Of the voice of the young, he says: “At the age of 4 to 6 days a liquid peeping was practically identical with the peeping of baby long-eared owls. Snapping of the mandibles was not noted until after the sense of fear had been developed, at the age of 16 to 17 days.

A rasping, sibilant call, heard from the nest after dark, was presumably the hunger call of the nestlings, and might be expressed thus: i-z-z-z-z-2-z-z. This call soon brought one of the parents which voiced its anger, or distress, in a very similar manner, though more insistently as it flew back and forth near the nest, even brushing me with its wings occasionally. This hissing might best be likened to the sound made by jets of steam escaping from a small nozzle.”

Plumages: When first hatched the young saw-whet owl is clothed in white down, which is worn for probably the first ten days or two weeks. This down then begins to be pushed out and replaced gradually by the juvenal, soft, downy plumage, which is not complete until the young bird is about four weeks old or older; between the ages of three and four weeks the tips of the first down are wearing off and the wings are growing rapidly, so that the young bird will soon be able to fly.

In the full juvenal plumage the young saw-whet is a beautiful creature, a really lovely little owl. The upper parts are deep rich browns, “auburn” on the head and hind neck, shading off to a paler shade of the same color on the upper breast and to “Mars brown” on the back and wings; the plumage of the head is particularly full and fluffy, making it seem over large; the facial disks are “Mars brown”, and there is a large, conspicuous, white, V-shaped patch extending from the base of the bill lip over the eyes; the middle and lower breast is “ochraceous-buff”, shading off to “warm buff” posteriorly; the wings and tail are as in the adult.

This plumage is worn well into, or entirely through, the summer, depending on when the bird was hatched, when a complete molt of the contour plumage takes place, producing the first winter plumage, which is practically adult. I have seen this molt well advanced on July 25 and only just beginning on September 3; the molt begins in the face and on the under parts. Adults apparently have one complete annual molt from August to November.

Food: The food of the saw-whet owl consists mainly of mice, especially woodland mice, small rats, young red and flying squirrels, chipmunks, shrews, bats, and other small mammals. A few small birds, such as sparrows, june05, and warblers, have been recorded in its food; and a few insects are occasionally eaten. Dr. A. K. Fisher (1893b) reports that “of 22 stomachs examined, 17 contained mice; 1, a bird; 1, an insect; and 3 were empty.” He also says: “In winter Mr. Comcau once saw one of these little owls fly from the carcass of a great northern hare that had been caught in a snare. The owl had eaten away the abdomen and was at work within the thoracic cavity when frightened away.”

Illustrating the patience of this owl, as a mouser, Lewis 0. Shelley has sent me the following note: “One winter, near zero weather with snow on the ground, a saw-whet owl was noticed as it perched on a sapling maple close to a back stoop at a dwelling flanked on the back and sides by woodland. The woman of the house occasionally placed pies outside to cool quickly, and mice as surely found the pastry. Perhaps the owl had seen a mouse at such a time, and when on a succeeding day a pie was put out, and the lady of the house was where she could watch it, she saw the owl perched again in the maple tree. Then a mouse crept forth and the owl’s patience was rewarded, when it glided down and made its catch, making off into the woods with the mouse in its claws.”

Major Bendire (1877) once had one in captivity, of which he says: “This I fed at first on live mice, the only thing it would touch, but after a while it ate the carcasses of birds, and would eat twice its own weight in a day. If several whole birds were thrown into its cage it would eat the heads of all of them first, and hide the bodies in the corners of the cage, covering them up with loose feathers. Once I put a red winged blackbird, perfectly unharmed, in the cage with it, which it at once killed. Flying to its perch it grasped it with two of its toes in front and two in rear, and always sat in this manner. I kept it supplied with fresh water, but I think it never used any.”

Although this owl is mainly useful and beneficial in its feeding habits, it is a powerful and savage little fellow at times and capable of killing birds and animals larger than itself; that it can be very destructive is well illustrated by the following story, related by J. A. Farley (1924):

Mr. E. Cutting of Lyme, New Hampshire, once told me that in the fall a few years ago 1~e found that sometl~ing was killing his Pigeons. He thought it might be a mink or a weasel or some other animal. He had 25 Pigeons that roosted nightly on sticks put up for perches in his barn. The dove-hole was close by in the barn door. Seven Pigeons lay dead one morning on the hay beneath their perches. The birds’ heads were gone, some feathers were lying about and there was some blood on their bodies; otherwise there was no sign. The following evening Mr. Gutting went by stealth into his ham. By the light of his lantern he found two more headless Pigeons on the hay. Looking up he saw the “killer” perched on a beam. He despatched it with a long stick. It was a Saw-whet Owl.

Rockwell and Blickensderfer (1921) quote George L. Nicholas as follows: “While hunting in a pine wood near this town ISuminit, New Jersey], I obtained an Acadian [saw-whet] owl. Upon dissecting it I found that its stomach contained a flying squirrel, which had been swallowed whole and but slightly digested.”

Behavior: The one characteristic most prominent in the behavior of the saw-whet owl is its tameness, stupidity, or fearlessness; it can be approached most easily, even within a few feet, and has often even been caught in the hand, or under a hat, when carefully approached. Sometimes it shows marked curiosity, or sociability. Taylor and Shaw (1927), writing of their experience with it in Mount Rainier National Park, say:

This, perhaps the most interesting owl in the park, is one with which the camper is most likely to become acquainted, for the saw-whet seems to be a victim of uncontrollable curiosity. One evening, just at dusk, as several members of the party were seated about the camp fire at Owyhigh Lakes, one of these little owls flew into camp and perched, quite unconcerned, on a tree near the fire, as if wishing to join the circle.

Another owl did the same thing at Sunset Park; and at St. Andrews the evening twilight was made particularly interesting by the movements and curious call notes of saw-whet owls. Their interest in our camp was very obvious. On more than one occasion their curiosity, or stupidity, maybe, drove them into our tent. A peculiar sensation it was, to waken suddenly and hear the call of an owl sounding within 6 feet of one’s ear, followed soon by the soft flutter of wings as the bird left the tent.

They appeared to be most active at dusk and again an hour or so before daybreak.

Cantwell describes their flight as quite unlike that of other owls, partaking more of the nature of the labored undulating flight of the small woodpeckers. Shaw says their flight is Rapid for an owl, giving the bird a sprightly appearance not observed in others. This peculiar flight helps identify individuals encountered in the daytime.

My own impressions of its ffight agree with those of Dr. Fisher, who says (isoab): “The ffight resembles that of the woodcock very closely, so much so in fact, that the writer once killed a specimen as it was flying over the alders, and not until the dog pointed the dead bird was he aware of his mistake.”

The saw-whet owl is essentially a woodland bird, oftener found in the dark recesses of coniferous woods than in the more open growth of the deciduous forest, with perhaps a preference for swampy woodlands rather than the well-drained uplands. It is seldom seen in the high treetops but prefers to hunt, or to doze during the day, at the lower levels, often within a few feet of the ground. On May 28, 1925, while looking for sharp-shinned hawk nests, in a large, dense grove of white pines in Lakeville, Mass., I noticed the broken-off top of a small pine that had lodged, about 10 feet from the ground, against another pine; an accumulation of sticks and rubbish, suggesting a crude nest, had lodged in the top, which tempted me to give the tree a kick; much to my surprise a saw-whet owl flew out and alighted on a low branch of a pine within a few feet, where it sat and stared at me. I examined the fallen top carefully but could find nothing of interest; but I judged from the number of white droppings and pellets, on the ground below it, that this was the day roost of the male owl. There was probably a nest somewhere in the vicinity, but a protracted search failed to reveal it.

A different type of roost is described by Richard F. Miller (1923) as follows:

On April 5,1922, at Holmesburg, Philadelphia, Pa., while searching the upper border of a strip of woods, for a Cardinal’s nest, I almost bumped my head against a Saw-whet Owl that was roosting under a dense canopy of honeysuckle vines, five feet high, that covered one of the bushes. The bird flew about fifteen feet and lit on a limb of a bush, a yard from the ground, with its back towards me. It permitted me to approach within two yards, turning the head around to watch me. It then flew about four yards and lit at the same height upon another bush. I approached within three yards before the bird flew to another perch, about ten yards away; both of these times it faced me and quietly and unconcernedly let me approach. It seemed utterly fearless, and gazed at me with wide opened eyes. Under its roost was a pile of 31 pellets, and two feet distant was a similar roost, under a dense canopy of Lonicera vines; beneath this one were 35 pellets, altogether 66 pellets beside pills of excrement, indicating that the bird had spent the winter here.

Except by some chance encounter, as related above, even the keenest human eyes are not likely to discover thisdiminutive owl, perched silent and motionless in dense foliage, unless its presence is indicated by the excited activity and noisy protests of its small bird enemies, such as sparrows, warbiers, chickadees, and kinglets, that always show their hatred and fear of all owls.

Voice: The far-famed saw-filing notes are far from being the only, or even the commonest, notes uttered by this versatile little owl. William Brewster (1925) has deeribed several of these in his notes from Umbagog Lake, Maine. Of the saw-ffling notes, he says: “They may be heard everywhere in the forest in February and March; oftenest just before daybreak, not infrequently throughout the night, occasionally in the daytime during cloudy weather when they are thought to presage rain. The saw-filing season reaches its height in March and usually ends before the first of May, although it may continue intermittently through that month and even into the first week of June.” On May 18 “they were given at infrequent intervals and always in sets of threes thus:: skreigh-dw, slcreigh-dw, skreigh-dw. Their general resemblance to the sounds produced by filing a large mill-saw was very close, I thought.” On May 28, he heard a somewhat different, metallic note; the owl “kept it up for a little more than a minute, regularly uttering four apparently monosyllabic notes every five seconds. Their metallic quality was so pronounced and their tone so ringing that they reminded me of the anvil-like tang-tang-tang-ing with which a species of Bell Bird makes the tropical forests of Trinidad resound. To this, indeed, they bore no slight resemblance, although much less resonant and far-reaching. Nor did they fail to suggest saw-filing also.” The above notes were heard near mid-day, but, at 9 p. m. on June 4, one “was heard to uncommon advantage, not only because of his nearness, but also because the calm night air remained undisturbed by sounds other than those he produced. Whurdle-whurdle-whurdle he called long and uninterruptedly, m a whistling voice obviously quite devoid of ringing or even metallic quality, and very like that of the Glaucidium of Trinidad, but somewhat more guttural. All his utterances were rapidly delivered, evenly spaced, and precisely alike. They altogether failed to suggest the sound of saw-filing.” One, circling about the camp on two evenings, September 26 and October 5, “uttered a single staccato whistle, not unlike the familiar pheu of Wilson’s Thrush, but decidedly louder and clearer. This was repeated at intervals of half a minute or less for some time.” This was then replaced “by a gasping and decidedly uncanny ak-h-h something like that of a Barred Owl, but feebler and less guttural.” Another “gave in quick succession four whistles:: hew-h~u,-hew-hew.”

W. Leon Dawson (1903) says that the principal note he has heard “is a rasping, querulous sa-a-a-a-ay, repeated by old and young with precisely the same accent, and inaudible at any distance above a hundred feet.” The young also make a hissing sound, which is probably a food call, and a bat-like squeaking; Mr. Brewster (1882b) says that this squeaking was discontinued shortly after molting, when it began a new, whistling cry; “this utterance consists of a series of five or six low, chuckling but nevertheless whistled calls, which remind one of that peculiar, drawling soliloquy sometimes indulged in by a dejected hen on a rainy day.”

The courtship notes are referred to above. The interesting belllike note, with its curious ventriloqulal quality, so graphically described by Audubon (1840), is probably also a courtship call. Mr. Terrill tells me that the saw-filing note is “not much louder than the rasping song of the katydid, and in fact is almost as suggestive of a grasshopper as a bird; it might be described as t-sch: whet-t.”

Field marks: The saw-whet owl is the smallest of our eastern owls, considerably smaller than the screech owl; it is, however, considerably larger than the pygmy owls. It differs from the screech owls in having a rounded head with no ear tufts. It might easily be confused with the much rarer Richardson’s owl, which is only slightly larger, but it has a black instead of a yellow bill; it lacks the black rim of the facial disk, so prominent in Richardson’s owl, and the top of its head is streaked, instead of spotted.

Fall: The saw-whet owl has generally been recorded as a resident species, but it evidently migrates to some extent, or at least wanders widely, in fall. As with many other apparently resident species, the species may be present at all seasons in regions where the summer and winter ranges overlap, but there has been a general southward movement of individuals. W. E. Saunders (1907) and P. A. Taverner and B. II. Swales (1911) have shown evidence of a heavy migration of these owls in Ontario in 1906, as revealed by the disastrous effects of a severe storm. Taverner and Swales (1911) write:

The first indication we received of any strong migratory movement in this species was when W. E. Saunders of London, Ont., received word from Mr. Tripp of Forest, Out., of a migration disaster on the shores of Lake Huron, October 18, 1906. His investigation of this occurrence was reported in “The Auk.” He discovered the shore of the lake in the vicinity of Port Franks covered with the waterwashed bodies of birds that had been overwhelmed in a storm, likely while crossing the lake; and though he covered but a small portion of the affected territory and did not touch upon its worst part, he counted 1,845 dead birds in two miles of shore. Here was evidently a disaster that overcame a large movement of mixed migrants but the salient fact in this connection is, that he counted 24 Saw-whet Owls among the debris. Mr. Saunders is, and has been for the last twenty-five years, a most keen and enthusiastic field worker, but in summing up his experience with the species, says: “The Saw-whets were a surprise. They are rare in western Ontario, and one sees them only at intervals of many years, evidently they were migrating in considerable numbers.”

A statement elicited from the captain of the fish boat “Louise” of Sandusky. Ohio, bears very closely upon this subject. He says, that about October 10, 1903, when on the steamer “Helena”, off Little Duck Island, Lake Huron, he saw a large migration of small owls and that many of them lit on the steamer. His description tallied very well with that of this species and there is the probability that it was a relay of this same migration that was so hardly used in 1906.

In an adjacent sod quite comparable station, Long Point, on Lake Erie and sixty miles to the east, we had beard that Saw-whets were at times captured in numbers by stretching old gill nets across the roads in the woods. The birds flying down the clear lanes became entangled in the meshes and thus caught.

[While working though the red cedar thickets on this point, on October 15, 1910], within less than two hours, and in a small part of the thickets, we discovered twelve of these owls. We looked carefully for the young, the elbifrons plumage, but without success.

All birds seen were alert and the majority in the densest red cedar clumps. Most of them were close up against the trunk of their respective trees, and usually about six feet from the ground, the highest being about twelve feet, and the lowest four. None showed any fear. But one flushed, and that was only when the tree it was on was jarred in our passage; even then it flew but a few yards and allowed our close approach. None uttered any sound except the usual owlish snapping of the bill.

Here, then, are records of four migrational massings of this hitherto supposed resident owl. It was too early in the season to explain their gatherings as “winter wandering in search of food”, and the close tallying of all the dates point to the conclusion that from the middle to the end of October the Saw-whet Owls migrate in considerable numbers, but from their nocturnal habits and secluded habitats while en route are seldom observed.

Winter: When the weather is not too severe and the ground is not too deeply covered with snow, I believe that some of these little owls spend the winter as far north as northern New England. They seldom, if ever, I think, perish by freezing to death, if they can find sufficient food to keep up their vitality; but when the mice are all living in their tunnels under the snow, and most of the small birds have gone south, the poor owls are hard pressed for food, become very much weakened, and may succumb to the cold. Forbush (1927) writes:

In winter in the great coniferous forests of Canada much of the snow is upheld on the branches of the trees in such a way that there are spaces here and there close to the trunks where there is little snow. There the wood mice come out at night from their hiding-places under the snow, and there the little owl perched in the branches above them awaits their coming; but if for any reason owl-food is scarce or hard to obtain, as sometimes happens in severe winters with deep snow, the little owls must move south or perish. At such times, as in the winter of 1922: 23, when Acadian Owls were abundant in New England, there was a great influx of these birds from the north. By the time they reach a milder clime, many of them are too emaciated and exhausted to hunt or even to eat. They seem to lose all interest in life, and seek only a quiet retreat in which to die. Others more hardy or less exhausted survive to return, with the advent of spring, to the land of their nativity.

Mr. W. E. D. Scott took not less than twenty-one specimens during December 1878, in a cedar grove on a side hill with a southerly exposure, near Princeton, New Jersey. He found some of them very tame and unsuspicious, allowing themselves to be taken by hand; I have also found them equally stupid in the vicinity of Camp Harney, Oregon. Each winter one or more specimens were brought to me alive by some of my men, who found them sitting in the shrubbery bordering a little creek directly in the rear of their quarters, where they usually allowed themselves to be taken without making any effort to escape. I thought at first that they were possibly starved, and on that account too weak to fly, but on examination found them mostly in good condition and fairly fat. They seem to be especially fond of dense evergreen thickets in swampy places or near water courses.

It is hard to account for the large number of saw-whet owls that have been picked up dead in all sorts of places, unless this species is endowed with an especially delicate constitution, which requires an unusual amount of food. Even so, it seems hardly likely that they could have starved to death in the vicinity of Washington, D. C., where many have been picked up, or in the desert regions of California and Oklahoma, where their remains have been found, as the climate is mild and food available in all of these places. It may be, as Mr. Forbush has suggested above, that they were too far gone when they reached these places.

Mr. Terrill writes to me, from the Montreal region: “I have records for every month, but it is notable that I have recorded twice as many in December as in any other month. One must, of course, discount the suggested increase in December owing to the fact that some of them were seen in bare deciduous thickets. Nevertheless, there is undoubtedly a decided migratory movement of this owl in early winter, at least periodically, as they are frequently observed in places where I am satisfied they do not breed.”

Breeding range: The breeding range of the saw-whet owl extends north to southeastern Alaska (Forrester Island); central Alberta (Carvel, Red Deer, and Stony Plain); Saskatchewan (probably Osler and the Qu’Appelle Valley); Manitoba (Aweme and probably Kalevala); Ontario (probably Moose Factory); and Quebec (Lake Mistassini, probably Godbout, and Anticosti Island). East to Quebec (Anticosti Island, forks of the Cascapedia River, and the Magdalen Islands); Nova Scotia (Sydney, Pictou, Wolfvillc, and Ilalif ax); Maine (Calais and Bucksport); New Hampshire (Tamworth and Franklin Falls); Massachusetts (Bridgewater, Taunton, and Wareham); Connecticut (Chester); New York (Millers); and western Maryland (Cumberland). South to Maryland (Cumberland); probably rarely northern Pennsylvania (Titusville); Ohio (probably Cleveland and probably Columbus); northern Indiana (Waterloo and Kentland); Illinois (probably Chicago); central Missouri (Bluifton); Nebraska (Nebraska City); Oklahoma (near Tulsa); probably Colorado (Dome Rock and Breckenridge); north-central Arizona (San Francisco Mountains); and southern California (San Gabriel Mountains). West to California (San Gabriel ~vIountains, Fyfee, and the South Fork Mountains); Oregon (Newport and Beaverton); Washington (Yakima and probably Owyhigh Lake); British Columbia (Chilliwack and Masset); and Alaska (Forrester Island).

Winter range: The winter range of this little owl extends north to British Columbia (Okanagan); central Alberta (Glenevis, Mundare, and Flagstaff); Saskatchewan (Eastend and Osler); Manitoba (Minnedosa); southern Ontario (Listowel, Guelph, Algonquin Park, and Ottawa); and Quebec (Montreal and probably Anticosti Island). East to Quebec (probably Anticosti Island); New Brunswick (Scotch Lake and Oak Bay); Maine (Calais and Portland); Massachusetts (Ipswich, Boston, and Taunton); Rhode Island (Kingston); Long Island (Orient); and New Jersey (Princeton, Camden, and probably Cape May). South to New Jersey (probably Cape May); Maryland (Baltimore, Laurel, and College Park); the District of Columbia (Washington); Ohio (Medina and Sandusky); southern Illinois (rarely Mount Carmel and probably Anna); Missouri (St. Louis); Kansas (Manhattan); Colorado (Denver and Salida); rarely New Mexico (Santa Fe and Silver City); southern Arizona (Huachuca Mountains, and Pima County); and southern California (Big Creek). West to California (Big Creek, Quincy, Point Reyes, probably Sonoma, and Oakland); Oregon (Gardiner and The Dalles); Washington (Kiona, Seattle, and Bellingham); and British Columbia (Okanagan).

Migration: The movements of the saw-whet owl are too erratic to be considered as true migration, and it will be observed that there is little difference in the breeding and wintering ranges outlined. Nevertheless, it is probable that in winter the individuals in the northern parts of the breeding range generally withdraw to the southward. Furthermore, during some winters the species becomes much more numerous in certain parts of its winter range. At such times a heavy autumnal flight may have preceded the concentration. Such flights usually take place in October but they are sometimes delayed until late in December.

In southern Ontario a large flight was recorded in the fall of 1889, again during the period October 10 to 28, 1895, and a third on October 10, 1906. On the latter occasion large numbers were killed by a storm while crossing Lake Huron.

The saw-whet is rarely seen in southern latitudes after the latter part of March.

Casual records: There are a number of recorded instances of this species in regions that are outside of the normal range. Among these are the following:

One was seen at Lewisburg, WV. Va., on December 24, 1914. In Virginia one was reported from Parksley on December 10, 1889; another was taken at Cowart on November 26, 1902; and a third was seen at Blacksburg in January 1912. A mounted specimen was exhibited at the fair at New Bern, N. C., in 1892; an adult female was collected at Raleigh, on December 18, 1894; and another was taken in Wake County, on December 4, 1897. South Carolina has at least four records: a specimen with incomplete data from St. Helena Island; one collected on November 11, 1909, at Weston; one taken at Aiken in February 1899; and one seen by Wayne at Mount Pleasant on December 24, 1885. A specimen taken on Tybee Island, Ga,, January 1,1911, was identified at the Biological Survey. One was collected at Madisonville, La., in December 1889.

Macoun lists the species as a “not uncommon summer migrant” in Newfoundland but gives no additional details. In Bermuda, on January 12, 1849, one was found sitting inside the muzzle of a gun and was kept alive for several days. Another was reported to have been seen in the same locality a short time afterward.

The status of the few saw-whets that have been reported from Mexico and Guatemala is somewhat uncertain, but they are considered a distinct race by some authors.

Egg dates: New York and New England: 12 records, March 19 to July 3; 6 records, April 10 to 30, indicating the height of the season Ontario to New Brunswick: 3 records, April 6 and May 23 and 28.

Washington and Oregon: 2 records, April 12 and May 2.

now Northern Saw-whet Owl – Aegolius acadicus QUEEN CHARLOTTE OWL CRYPTOGLAUX ACADICA BROOKSI (Fleming)

A dark race of the saw-whet owl was first recognized and described by Dr. Wilfred H. Osgood (1901), and called the northwest saw-whet owl (Nyctala acadica scotaea) ; the type was collected at Massett, Queen Charlotte Island, British Columbia, on December 19, 1896. The characters given for it are: “Similar to N. acadica, but darker both above and below, dark markings everywhere heavier; flanks, legs, and feet more rufescent.” He says further in regard to it: “This darkcolored form of the Acadian owl doubtless ranges throughout the humid Pacific coast region. The only specimens that I have examined beside the type are several imperfect ones from Puget Sound, which are in the National Museum collection. These agree with the type in richness of color and extent of dark markings.”

Ridgway (1914) treated scotaea as a synonym of acadica, after examining the type of the former and other material available, for he says:

I am not able to make out any geographic variation in this species except a slight average difference in the hue of the brown of the upper and under parts, which is reddest in examples from the Pacific coast district (British Columbia to southern Mexico), more grayish brown in those from the Rocky Mountains, intermediate, but nearer the former, in those from the Atlantic side. The only peculiarities that I am able to observo in the type of Nyctala acadica scotaea consist in the deep ochraceous-buff auricular region and more reddish brown of the pileum; but I am of the opinion that these characters will not prove constant when more specimens from the Queen Charlotte Islands have been examined.

The Queen Charlotte owl (Cryptoglaux acadica brooksi) was named and described by J. II. Fleming (1916), based on three adult females and one immature bird, taken on Graham Island, in the Queen Charlotte group, and sent to him by J. A. Munro; he also examined two more, one of them a male. These are all very much darker than Osgood’s type of scotaea, in both sexes; for a detailed description the reader is referred to Mr. Fleming’s paper. He suggests that the type of scotaea may have been a stray from the mainland, as it is very different from the birds he has described as brook~si, which probably represent the resident race of the islands. That there may be another race on the Pacific coast, of which scotaea is typical, is a possibility; but Mr. Ridgway failed to recognize it, and Mr. Fleming says that it “is only approached by a bird from Queretaro, Mexico, and is much brighter than a male from Victoria, B. C., which in turn can be matched by Ontario birds.”

Injured Owl Rescued | Cute Saw Whet Owl | Released Back into the Wild

Nothing seems to be known about the nesting habits of this race; but we have no reason to think that, in these or other habits, it differs materially from the eastern race; its food and its plumage changes are apparently similar; the characters of the race are well emphasized in the juvenal plumage; its eggs are unknown, so far as I know.

About the Author

Sam Crowe

Sam is the founder of Birdzilla.com. He has been birding for over 30 years and has a world list of over 2000 species. He has served as treasurer of the Texas Ornithological Society, Sanctuary Chair of Dallas Audubon, Editor of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s “All About Birds” web site and as a contributing editor for Birding Business magazine. Many of his photographs and videos can be found on the site.

Northern saw-whet owl

The scientific description of one of the sub-species of this owl is attributed to the Rev. John Henry Keen who was a missionary in Canada in 1896. Adults are 17–22cm long with a 42–56.3cm wingspan. They can weigh from 54 to 151g with an average of around 80g. making them one of the smallest owls in North America. They are close to the size of an American robin. The northern saw-whet owl has a round, light, white face with brown and cream streaks; they also have a dark beak and yellow eyes. They resemble the short-eared owl, because they also lack ear tufts, but are much smaller. The underparts are pale with dark shaded areas; the upper parts are brown or reddish with white spots. They are quite common, but hard to spot.

Habitat

Their habitat is coniferous forests, sometimes mixed or deciduous woods, across North America. Most birds nest in coniferous type forests of the North but winter in mixed or deciduous woods. They also love riparian areas because of the abundance of prey there. They live in tree cavities and old nests made by other small raptors. Some are permanent residents, while others may migrate south in winter or move down from higher elevations. Their range covers most of North America including southeastern Alaska, southern Canada, most of the United States and the central mountains in Mexico. The map shows where they breed and the areas where they can live throughout the year.

Some have begun to move more southeast in Indiana and neighboring states. Buidin ”et al.” did a study of how far north the northern saw-whet owls breed and they found that they can breed northward to 50º N, farther than ever recorded before. Their range is quite extensive and they can even breed in the far north where most birds migrate from to breed. They are an adaptive species that can do well in the cold.

Food

These birds wait on a high perch at night and swoop down on prey. They mainly eat small organisms with a FOCUS on small mammals in their diet. A test done by Swengel and Swengel found that the northern saw-whet owls most often eat deer mice, 67% and voles, 16% of the time in Wisconsin. A similar test done by Holt and Leroux in Montana found that these owls ate more voles than other mammal species. This shows that these owls can change their main prey depending on what is available. Also researched by Holt and Leroux was the eating habits of northern saw-whet owls and northern pygmy owls and found that they prey on different animals for their main food source, showing that they can adapt not only depending on the prey but also with the other predators in the areas where they live.

Other mammals preyed on occasionally include shrews, squirrels. various other mice species, flying squirrels, moles and bats. Also supplementing the diet are small birds, with passerines such as swallows, sparrows, kinglets and chickadees favored. However, larger birds, up to the size of rock pigeon can even be taken. On the Pacific coast they may also eat crustaceans, frogs and aquatic insects. Like many owls, these birds have excellent hearing and exceptional vision in low light.

Defense

Northern saw-whet owls lay about 5–6 white colored eggs in natural tree cavities or woodpecker holes. The father does the hunting while the mother watches and sits on her eggs. Females can have more than one clutch of eggs each breeding season with different males. Once the offspring in the first nest have developed their feathers the mother will leave the father to care for them and go find another male to reproduce with. This type of mating is sequential polyandry. They compete with boreal owls, starlings and squirrels for nest cavities and their nests may be destroyed or eaten by those creatures as well as nest predators such as martens and corvids. Saw-whet owls of all ages may be predated by any larger species of owl, of which there are at least a dozen that overlap in range. They are also predated by ”Accipiter” hawks, which share with the saw-whet a preference for wooded habitats with dense thickets or brush.

Cultural

Martin from the “Guardians of Ga’Hoole” novel series is a northern saw-whet owl.

The call of the saw-whet owl is mentioned in the Grateful Dead song “Unbroken Chain” on their album ”Grateful Dead from the Mars Hotel”.

After an online “Critter Vote”, the saw-whet owl became the new star of Telus’ mobility campaign in the summer of 2011.

References:

Some text fragments are auto parsed from Wikipedia.

| Kingdom | Animalia |

| Division | Chordata |

| Class | Aves |

| Order | Strigiformes |

| Family | Strigidae |

| Genus | Aegolius |

| Species | A. acadicus |

Northern Saw-whet Owl

Northern Saw-whet Owls are one of the smallest owls in North America, with them being about the size of a robin.

They have tiny brown bodies but large round heads with fine white streaks. Their eyes are bright yellow with thick white feathers forming a “Y” in between them.

Their backs and wings are brown with white spots. Their chests and bellies are white with brown streaks.

Juveniles have plain brown heads and very visible white eyebrows on brown facial discs. Their underparts are plain cinnamon brown, and they also have no spots on their backs.

- Aegolius acadicus

- Length: 7.1 – 8.3 in (18 – 21 cm)

- Weight: 2.3 – 5.3 oz (65 – 151 g)

- Wingspan: 16.5 – 18.9 in (42 – 48 cm)

Range

Northern Saw-whet Owls are usually resident all year in Canada, northern US states, and western US states. However, they may migrate to lower areas in winter to the rest of the US.

Habitat And Diet

You can find Northern Saw-whet Owls in dense coniferous forests where they roost hidden among the thick branches and foliage. However, they like it near an open area and water source where they hunt.

They are nocturnal, so they hunt mostly mice from a perch at night. They may also

Nests

Nests of Northern Saw-whet Owls are tree cavities that have been left from other species, such as Pileated Woodpeckers. They do not add any other nesting material and instead lay their eggs directly on the debris.

The female lays four to seven eggs that take four weeks to incubate. The male’s job is to bring the female food while she’s incubating.

Attracting Northern Saw-whet Owls to your backyard is possible with a nest box if you are in range and have lots of trees.

Fun Fact:

The Northern Saw-whet Owl got its name from its repeated tooting whistle, or the “skiew” sound that it makes when it’s alarmed or threatened. The sound is similar to the whetting of a saw.

Североамериканский мохноногий сыч Aegolius acadicus (Gmelin, JF, 1788)

- acadicus (Gmelin, JF, 1788)

- brooksi (Fleming, JH, 1916)

Не классифицировано

- Подвид не указан

- Фоном к другой записи

Благодарности

Ranges shown based on BirdLife International and NatureServe (2011), now curated and maintained by Xeno-canto.

Другие ресурсы

Примечание: Xeno-canto follows the IOC taxonomy. External sites may use a different taxonomy.

Seasonal occurrence

- Резидент

- Гнездится

- Не гнездится

- Пролет

- Неопределенный

313 записей переднего плана и 30 фоновых записей Aegolius acadicus. Общая длительность записей 5:27:12.

Male advertising toots recorded on a north-facing slope in an open forest with Jeffrey pine, incense cedar, white fir, sugar pine, and canyon live oak.

Equipment: Sony PCM-M10 recorder, Sennheiser ME62 microphone, and a Telinga 22 inch parabola hand-held.

Male advertising toots recorded at a range of roughly 10 meters in moderately windy conditions.

Equipment: Sony PCM-M10, Sennheiser ME62, and a Telinga 22 inch parabola hand-held. Edits: trimmed. No normalization: I had to dial down the gain to avoid saturation.

Male advertising toots recorded at a range of roughly 10 meters in moderately windy conditions.

Equipment: Sony PCM-M10, Sennheiser ME62, and a Telinga 22 inch parabola hand-held. Edits: trimmed. No normalization: I had to dial down the gain to avoid saturation.

Male advertising toots recorded in windy conditions on a north-facing slope with white fir, sugar pine, Jeffrey pine, and canyon live oak.

I edited out about 20 seconds of the recording in the middle. Then I normalized the file to.3 dB.

Equipment: Sony PCM-M10, Sennheiser ME62, and a Telinga 22 inch parabola hand-held.

Calls, not toots. Recorded on a north-facing slope in an area with Jeffrey pine, sugar pine, white fir, incense cedar, and canyon live oak.

Equipment: Sony PCM-M10, Sennheiser ME62, and a Telinga 22 inch parabola hand-held. Audio levels in the two channels were very different. Trimmed and normalized to.3 dB.

No modifications were made to this recording. It is an extract from an overnight recording in a remote mountainous region. Habitat is mixed conifer and deciduous forest intercut with grassland/sagebrush. The bird was not observed.

Первоначально загадочная запись. Посмотреть форум.

No modifications were made to this recording. It is an extract from an overnight recording in a remote mountainous region. Habitat is mixed conifer and deciduous forest intercut with grassland/sagebrush. The bird was not observed.

Первоначально загадочная запись. Посмотреть форум.

Male advertising toots recorded at a range of about 10 meters while the bird was perched in thick trees (either Jeffrey pine or white fir).

Equipment: Sony PCM-M10, Sennheiser ME62, and a Telinga 22 inch parabola hand-held. Edits: trimmed and normalized to.3 dB.

Male advertising toots recorded at a range of about 10 meters while the bird was perched in thick trees (either Jeffrey pine or white fir).

Equipment: Sony PCM-M10, Sennheiser ME62, and a Telinga 22 inch parabola hand-held. Edits: trimmed and normalized to.3 dB.

Unmodified recording, part of the predawn long recording made of American Woodcocks. Recordist stood at side of road with open field on one side (where woodcocks were) and pine plantation on opposite side (where owl probably was). Half moon bright, but still too dark to see owl. Temp. 40 degrees.

Toot series, heard a few minutes before dawn, at close range. Next to a lake in a heavily forested area. I was not able to get a visual on the bird.

Played a skiew call for bird in XC766381, the bird shifted locations and started this alarm call.

After attempting to locate the bird in recording XC766381 it didn’t move, but started this rather odd alarm call remaining in approximately the same place

Bird immediately started singing its primary song when recording of primary song was played. Habitat was dense grove of Russian Olive Trees

Bird was in a thick stand of Russian Olive trees and is reacting to the playback of an alarm call of a Long-eared Owl

Bird was in a thick stand of Russian Olive trees.

XC710126 is the first recording; this is the second recording; not seen; two birds, one of which would occasionally give a “kew series” (Pieplow; also as ‘keek series’), after which the primary bird would immediately switch to very quiet song, gradually building up to loud, e.g., after 1:39, 3:10, 4:23, 7:31, 8:24 (faint; when the primary bird went quieter at other times, it may have heard what I did not record); 9:17 (primary bird changed to excited cadence), 10:16, 12:26, 14:42, 15:03, 16:59 (but ugly mic handling, sorry); over a half hour period, no indication the bird moved, just changed volume; I did not adjust the gain at all; ugly period where I moved 10:42 to 11:02, interval shortened at 11:27; some cosmetic editing in the last 5 minutes I did not keep track of; shortened at 17:26 to remove a partial ann.; shortened at 17:46, chitter at 18:05; also a different call at 0:35 and another rising note at 14:30, species ?;

not seen; Sunny Flat CG; unusual location, but the species was reported here often last spring and bred in South Fork in 2021 (normally expected at 2500m in mixed conifer forest; here found in Madrean woodland of junipers, oaks, and sycamores); interval shortened at 1:08; noisy generator; first of two recordings; interval shortened at 2:00, now away from the generator, but some wind in the canopy; large moon shortly after the last bit of light in the western sky; at 7:03, a second bird can be heard very softly giving a ‘keek series” (Pieplow), after which the primary bird immediately changes cadence and lower the volume, which was to happen regularly in the second recording; second recording is XC710127;

Natural cadence, continued after end of audio but cropped there because of interference from background campground noise.

Series of 4 “wails”. remote (unattended) NFC monitoring station on outskirts of small town (Millbrook). NSWO(s) present from late fall through winter.

Unmodified recording, series of 6 loud “kew” calls recorded at remote (unattended) NFC station on outskirts of Millbrok Ontario.

Unmodified recording, series of 6 loud “kew” calls recorded at remote (unattended) NFC station on outskirts of Millbrok Ontario.

Unmodified recording, overwintering Saw-whet Owl, series of 3 loud “wails” recorded at remote (unattended) NFC station on outskirts of Millbrok Ontario. Deep snow but owl(s) possibly surviving on mice attracted to two feeding stations. One, possibly two birds recorded regularly since late October. “kew calls”, “wails” throughout late fall and winter and “tooting” beginning in late January.

Please refer to XC668132 for the first Northern Saw-whet Owl recording. The bird in the present recording was in a maple tree opposite the scrubby area where I had recorded another of its species about 20 minutes earlier. That bird called consistently on one pitch and it was a lower pitch than the bird in this recording. The bird in this recording had a slightly higher voice, and its notes meandered slightly up and down in pitch. After it had called a while, the bird on the other side of the road began to call again. Since I was inbetween them, on foot, I had to choose which one to record, and chose to record this one. I hoped more of the notes of both birds would be recorded. I wondered if perhaps one bird was a parent and the other a juvenile, though it could have been a mated pair.

/Users/peterward/Desktop/Two Sennheiser directional microphones with Marantz cassette recorder.pdf

One of four Northern Saw-whet Owls along Flagstaff Road, fairly near the summit.

Xeno-canto.org is powered by the Xeno-canto Foundation and Naturalis Biodiversity Center

Website © 2005-2023 Xeno-canto Foundation

Записи © автор записи. Информацию о лицензии смотрите в подробностях записи.

Изображения сонограмм © Xeno-canto Foundation. Условия использования изображений сонограмм. те же, что и у записи, к которой они относятся.