Battle of Okinawa. Hacksaw ridge summary

Hacksaw ridge summary

Ten years and loads of tabloid covers passed between Mel Gibson’s previous directorial output Apocalypto and Hacksaw Ridge. Hollywood essentially blacklisted him for a decade partly for his deeply anti-Semitic remarks following a DUI arrest in 2006.

Hollywood, like America, loves second chances, and Gibson got one with this story of a man who went to war without fighting.

ONE SENTENCE PLOT SUMMARY: A conscientious objector and Army medic holds onto personal beliefs and saves dozens of lives without firing a shot during one of the bloodiest battles of World War II.

Hero (7/10)

Desmond Doss grew up as crazy as his old man. Fighting’, wrasslin’, gettin’ whoopins, Doss one day knocked his brother out with a brick during a scuffle. It set him straight.

Seeing the power of violence, Doss swears to never do so again. He also has an awakening one day in his early years, when he saves a boy’s life after a car fall on his leg. At the hospital that day he meets a right purty nurse.

Saving a life and meeting a hottie, such a day will change any man’s life. It’s love for that woman, love for his God, and, I guess, love for his country propelling Doss to join the Army and serve in his nation’s greatest hour of need.

Love for God and wife are unquestioned, but it’s the patriotism that remains an open question. As Doss explains to his father, all his buddies were “on fire to join up,” so he did too. Millions of other men felt the same way, joining because it seemed like the right thing to do AND because their buddies would be with them.

That’s certainly why Desmond’s father Tom (Hugo Weaving) joined the fight in World War 1. That war wrecked him, and his fingerprints are all over young Desmond and the movie.

Tom is a drunk who “hates himself,” and takes it out on his family. One day he was angry who who knows what, and he pulled a gun on his wife. Desmond scrambled in at the last moment to point the gun away. Tom fired it anyway, into the roof. No one was harmed, physically, but the moment stuck with Desmond. It was the last time he would touch a weapon.

Doss is a Seventh Day Adventist, a Christian faith with a Saturday Sabbath and a prohibition on violence. Doss has seen the destructive power of violence, and he will join the Army, not to kill, but to save lives. “With the world so set on tearing itself apart,” he says, “it don’t seem like such bad thing to me to want to put a little bit of it back together.”

With a sly grin and determined attitude, Doss graduates basic training, thanks only to a last-minute save from a brigadier general Tom Doss fought with. Congress protects the rights of military noncombatants to serve, and Doss will not be kept out of the Army for refusing target practice.

The first half of Hacksaw Ridge follows Doss in America. The second half takes him to the hell of Okinawa, late in the war. The actual battle is covered in later sections, but it’s the moments in between the shooting where Doss shines.

“Lord, help me get one more,” is Doss’s late-night mantra after the first day of battle atop the ridge. That night and next day, Doss rescues more than 80 wounded men, some of them Japanese, and sends them down the ridge to safety.

The movie depicts him working alone throughout the night, under enemy fire, and sending the men downward as if an angel. These actions earned him the Medal of Honor, and unbelievable achievement for a person who never fired a shot in battle.

Andrew Garfield plays Doss with unbridled conviction and a sunny disposition, even in the nastiest of environments. His initial trip to a hospital evokes kid-in-toy-store vibes. Kids don’t grow up to work in toy stores, but they can grow up to become medics covered in blood, as Doss does.

Villain (3/10)

You’d think the Japanese would be the villains, but that’s not true. Hacksaw Ridge poses the Army as the villain, a shocking idea for a World War 2 movie to have.

Doss is ridiculed and fought from day one in the Army. Howell calls him Private Cornstalk. Glover constantly asks him to drop the morals and get with the killing. He calls him “Son,” at least once, as clear a message of condescension as there is between men.

Doss is court-martialed for refusing orders, and he spends time in military jail. His barracks mates beat him bloody several times. Howell tells Doss, “It’s time you quit this.” Glover tells Doss, “Let the brave men go and win this war.”

The brave men do, and Doss is one of them. He never reneges on his beliefs. “It won’t be hard; it’ll be impossible.” That’s Papa Doss about trying to maintain one’s beliefs in a manic war. “If by some miracle chance you survive, you won’t be giving no thanks to God.”

Tom was wrong about Desmond. So were every soldier in the Army, and by movie’s end they all apologize for doubting him. Doss’s story is impressive and admirable, but he’s not like other men. Most folks picked up rifles and shot at their enemies. Many died. Doss did not, but he did suffer tuberculosis, which cost him a lung and five ribs.

Action/Effects (6/10)

The corn syrup budget must have comprised half the cash spent on Hacksaw Ridge. There’s plenty of gore to go around in the movie’s depiction of the siege of Hacksaw Ridge.

The movie’s first half deals with Doss’s trials (one literal trial) and tribulations from pledging to join the army to his deployment on Okinawa. The battle sequences are where the movie makes its mark.

Hacksaw Ridge is depicted as a large plateau on which are hundreds, perhaps thousands of embedded Japanese. Before Doss’s company climbs the ridge, we learn from the relieved unit that six times they tried to advance and six times they were thrown back. It’s the kind of carnage Papa Doss warned his boys about for years.

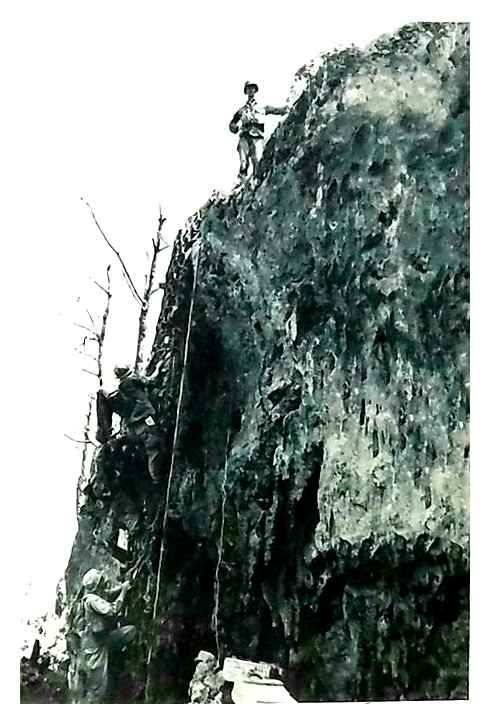

One day Doss and his brethren climb the rope ladder leading to the ridge. Rarely to people ascend into hell, but that’s what happens here. Blood drips on them from the recently shot.

The attack starts shortly after a naval artillery barrage on the ridge. Glover leads the assault into an area that resembles No Man’s Land. The soldiers walk over bodies, many of them torn in two in creative ways, always with an unhealthy does of guts trickling out like uncased sausage.

The Japanese strike before the smoke clears. Men are shot in the face and head in mid-sentence, beside their friends. A machine gunner is torn in half by bullets. Doss doesn’t wait long to save his first victim.

Smitty has a moment of grit. Pinned down behind a post, he uses the upper half of a dead body as a human shield, killing Japanese holding a crater. Smitty takes that crater.

It’s nasty up there. Gibson does a solid job orienting viewers during the chaos of the battle. Hacksaw Ridge, despite its height, is only a few steps from Hell. With all the pockmarks and rent iron, it’s hard to make sense of the landscape.

Yet the men have a clear objective. After taking an initial beating on the ridge, showing how the men react, the men reach a machine gun bunker. Dozens of Japanese fighters are inside and surround this bunker, and it’s clear the Americans must capture it to capture the ridge.

Hacksaw Ridge: The Battle of Okinawa

Howell leads the the attack. The GIs drop mortars and fire a bazooka at the concrete bunker, killing many but not stopping the barrage of bullets. Someone has an explosive device about the size of a backpack, and whoever tosses it inside the bunker will destroy it.

Volunteers creep ahead of the American line, into shell craters and out of sight of the enemy while his buddies lob the explosive pack toward him. One of Doss’s squad mates is the man to lob the device into the bunker. It explodes and rains concrete chunks onto the men.

That’s about it for battle sequences. Hacksaw Ridge is the story of a man who wouldn’t fight, so it does little good to show much fighting. However, those guys have to fight if Doss is to save them, and he spends most of the ensuing night and day doing so.

Credit to the crew for giving the battlefield a hellscape-ishness to it. That ridge could have been any battlefield. Nothing indicated it was on an island, in the Pacific, or that it occurred during World War 2.

Sidekicks (4/8)

Only Dorothy Schutte stands firmly beside her boyfriend/fiancé/husband. She’s a bird person, and into Doss from the get-go, as she agrees to attend a make out movie with him as their first date. When Doss kisses her, she slaps him, saying that he should have asked first.

Nothing wipes away that Doss smile, even when she’s mad at him for enlisting as a medic. He proposes to her at that moment, at her urging, and she agrees, only to say that she loves him but doesn’t like him much right now.

This gal’s got spunk. Unfortunately Hacksaw Ridge is a war movie and Schutte recedes after Doss leaves for basic training. She believes in her man, waiting at the altar for him on the day he’s thrown in jail for disobeying orders. Even her belief wavers. She tells Doss it’s just his pride and stubbornness preventing him from picking up a gun.

Henchmen (1/8)

Hacksaw Ridge has plenty of Japanese to die, and we’ll watch them perish in interesting ways. We know, thanks to the returning troops, that six times the embedded Nipponese have driven back the Yanks. They are formidable, but their days are numbered.

A single American flamethrower kills several Japanese, before one of them shoots the gas tank and explodes the American. Many more Japanese die from bayonet and take many americans in the same manner.

Doss spends a long sequence exploring their intricate tunnel system. We see him wander halls branching and forking and tall enough in which to stand upright. That comes as a surprise and hard to believe.

The Japanese try a dirty trick late in the movie. Haggard, dirty, and threadbare, a group of them raise the white flag. It’s a lie. The men in their underwear light grenades and toss them. Most GIs survive the dastardly attack. Did they try this in the actual battle? I’ll leave that to historians.

Stunts (3/6)

Mel Gibson movies, if you don’t know by now, are gory. He makes violence as if he’s paid by the gallon of gore. Hacksaw Ridge is no exception, of course, as dozens of mangled, red bodies and detached parts are on display, framed with only dirt, the less to distract you with.

You’ll see guys with a leg missing, two legs missing, legs detached, heads shot, and bodies on fire. Many, many bodies are burned by flamethrowers, more so than I believe took place in real life. Helps up the hellishness, though.

Doss does most of his work at night, sneaking around the deserted battlefield. He grabs an injured person and drags or carries him back to the ridge edge, ties him with his special knots, and lowers him dozens of feet to relative safety.

So there’s less stunt work than you might imagine for a war movie. No one is flying planes or driving tanks. A couple of naval barrages, possibly CGI, accompany the attacks. Hand-to-hand combat doesn’t last long either, as men are tired and stab each other with bayonets first chance they get.

That’s fine with me. World War 2 battles were long slogs. Many died from random shots, or were blown up with bombs, grenades, and mortars, of which we see plenty. Soldiers got tired or shot quickly, as is human nature. It’s hard to sustain life-or-death energy for too long.

Climax (1/6)

Doss spends a night alone saving man after man. His hands are bloody from running ropes. (Why not use a shirt on the ropes?) Next morning, he’s showing little signs of fatigue. Few living soldiers are left. One of them is Howell.

Doss approaches his commanding officer hours after first applying a tourniquet to his shot leg. Howell seems no worse for wear, and will probably live to be 95 if he can survive the afternoon. That will be a problem, as a sniper is currently attacking their position.

Howell targets the sniper after the enemy shoots Doss in his helmet, and kills him. Suddenly a bunch of Japanese are onto their position. They have to leave now. Doss asks for Howell’s rifle, the first and only time he’s touched a gun in his Army career.

But not to shoot it. Doss wraps a blanket around the gun, dragging Howell on it, while the latter shoots the approaching Japanese. They aren’t shot, but the enemy is angry. After Doss lets Howell down, he ties himself to a dead body and leaps over the edge as the Japanese approach. Doss’s buddies on below kill the overzealous enemies.

That’s not the end of the movie. The men are ordered to attack again the next day. Problem is, that’s Saturday, Doss’s Sabbath. Will he attack with them? His colleagues, for their part, refuse to fight without Doss their to drag them to safety.

Doss prays about it, and God apparently tells him it’s OK this one time to go into battle on Saturday.

So battle they do. Plenty of slow motion shooting and flame throwing accompanies the battle. We know what Hacksaw Ridge looks like, and Gibson sees little reason to go over it again.

The Japanese wave a white flag and emerge from a crater in their underwear. Turns out it was a dirty trick, as they light grenades and throw them at the surrounding Americans.

Doss is there, and he reacts by roundhouse kicking one lit grenade, which explodes and sends him twirling around. Now, finally, it is Doss’s turn to be dragged away.

And that just about wraps ‘er up. Actual footage ends the movie, showing the real Desmond Doss receiving the only Medal of Honor ever awarded to a conscientious objector. The real Doss speaks about his time in the war, as does the real Glover.

I found these videos the most touching moments of the movie. Perhaps a documentary would have been a better choice to tell this story. Then again, Hacksaw Ridge was up for Best Picture.

Jokes (2/4)

Howell is funny. You’d expect Vince Vaughn to be funny, and he is, but not in the way Vince Vaughn is usually funny. Many raised eyebrows must have accompanied news that Vaughn would play a drill sergeant in a war movie, but he does a fine job.

Nevertheless, he’s the man to hand out nicknames to the sorriest bunch of mud munchers he’s ever seen. The ghoulish-looking guy becomes Ghoul. The naked guy is Hollywood. Doss is dubbed Cornstalk. Good name. “Make sure you keep this man away from strong winds,” he says.

Setting (2/4)

I’ve said plenty about the placelessness of Hacksaw Ridge. I can’t decide if this helps or hurts the movie. I would like some idea of where Okinawa is, but all we get is Glover telling his men that if they take the island they can take Japan. Okinawa’s close by. I get it.

Commentary (2/2)

Is it fair to ask someone else to do your killing for you? Doss several times needs his fellow troops to kill Japanese because he won’t. I think it’s not. I support Doss’s stance of nonviolence, but his commanding officers make good points about the enemy. They won’t lay down their arms because he won’t pick one up.

However, why would Doss serve on the front lines? He’s a medic, and medics need to survive to save the shooters. He never should have been on that ridge during the first charge. Perhaps that’s failed movie logic and not the Army’s misguidedness.

“This is Satan himself we’re fighting.” That’s an Army psychiatrist evaluating Doss’s fitness for duty. The doctor thinks Doss is insane, after making a statement like that.

The doctor exemplifies all the wrong thinking about war. Considering the other side purely evil makes war easy to accept. It continues today and will continue for a long time. It’s why Japan thought it natural and right to attack the United States and invade all the places it invaded. The Axis of Evil shit needs to die. Doss was right. Violence doesn’t solve problems.

Offensiveness (0/-2)

No director makes more successful religious-friendly movies than Mel Gibson, not now, probably not ever. Desmond Doss has unusual beliefs (to WASPy Americans, though most Indians would find little strange about nonviolent vegetarians), but they are treated fairly.

Doss was an interesting subject for Gibson, who is well known for starring in violent movies and for making even more violent ones.

If offense is to be taken, it must come with its depiction of the Japanese. They are not a faceless enemy, but a voiceless one. Not as invisible as the Germans in Dunkirk, the Japanese in Hacksaw Ridge embody all stereotypes of Japanese soldiers–they are suicidal, they never give up, they are deeply embedded in the landscape.

Others

- (3) Automatic war movie bonus.

- During the battle Doss tells another soldier, “I never claimed to be sane.” He claimed exactly that to the Army psychiatrist.

- Not many movies feature a blood Cloud.

Summary (34/68): 50%

The soldier who wouldn’t fight, Desmond Doss, makes a good story, and in Hacksaw Ridge that story is well told. Six Oscar nominations, including Best Picture, and two wins, proved that Hollywood accepts Mel Gibson again. On to his remake of The Wild Bunch. Should be a bloodless afternoon at the cinema when that one hits the big screen.

Battle of Okinawa

The Battle of Okinawa was the last major battle of World War II, and one of the bloodiest. On April 1, 1945—Easter Sunday—the Navy’s Fifth Fleet and more than 180,000 U.S. Army and Marine Corps troops descended on the Pacific island of Okinawa for a final push towards Japan. The invasion was part of Operation Iceberg, a complex plan to invade and occupy the Ryukyu Islands, including Okinawa. Though it resulted in an Allied victory, kamikaze fighters, rainy weather and fierce fighting on land, sea and air led to a large death toll on both sides.

Okinawa Island

By the time American troops landed on Okinawa, World War II on the European front was nearing its end. Allied and Soviet Union troops had liberated much of Nazi-occupied Europe and were just weeks away from forcing Germany’s unconditional surrender.

In the Pacific theater, however, American forces were still painstakingly conquering Japan’s Home Islands, one after another. After obliterating Japanese troops in the brutal Battle of Iwo Jima, they set their sights on the isolated island of Okinawa, their last stop before reaching Japan.

Okinawa’s 466 square miles of dense foliage, hills and trees made it the perfect location for the Japanese High Command’s last stand to protect their motherland. They knew if Okinawa fell, so would Japan. The Americans knew securing Okinawa’s airbases was critical to launching a successful Japanese invasion.

Landing on the Beachheads

As dawn arrived on April 1, morale was low among American troops as the Fifth Fleet launched the largest bombardment ever to support a troop landing to soften Japanese defenses.

Soldiers and Army brass alike expected the beach landings to be a massacre worse than D-Day. But the Fifth Fleet’s offensive onslaught was almost pointless and landing troops could have literally swum to shore—surprisingly, the expected mass of awaiting Japanese troops wasn’t there.

On D-Day along the shores of northern France, American troops fought hard for every inch of beachhead—but troops landing on Okinawa’s beaches surged inland with little resistance. Wave after wave of troops, tanks, ammunition and supplies went ashore almost effortlessly within hours. The troops quickly secured both Kadena and Yontan airfields.

Japanese Army Waits

Japan’s 32nd Army, some 130,000 men strong and commanded by Lt. Gen. Mitsuru Ushijima, defended Okinawa. The military force also included an unknown number of conscripted civilians and unarmed Home Guards known as Boeitai.

As they moved inland, American troops wondered when and where they’d finally encounter enemy resistance. What they didn’t know was the Japanese Imperial Army had them just where they wanted them.

Japanese troops had been instructed not to fire on the American landing forces but instead watch and wait for them, mostly in Shuri, a rugged area of southern Okinawa where General Ushijima had set up a triangle of defensive positions known as the Shuri Defense Line.

Battleship Yamato

American troops who headed North to the Motobu Peninsula endured intense resistance and over 1,000 casualties but won a decisive battle relatively quickly. It was different along the Shuri Line where they had to overcome a series of heavily defended hills loaded with firmly-entrenched Japanese troops.

On April 7, Japan’s mighty battleship Yamato was sent to launch a surprise attack on the Fifth Fleet and then annihilate American troops pinned down near the Shuri Line. But Allied submarines spotted the Yamato and alerted the fleet who then launched a crippling air attack. The ship was bombarded and sank along with most of its crew.

After the Americans cleared a series of outposts surrounding the Shuri Line, they fought many fierce battles including clashes on Kakazu Ridge, Sugar Loaf Hill, Horseshoe Ridge and Half Moon Hill. Torrential rains made the hills and roads watery graveyards of unburied bodies.

Casualties were enormous on both sides by the time the Americans took Shuri Castle in late May. Defeated but not beaten, the Japanese retreated to the southern coast of Okinawa where they made their last stand.

Kamikaze Warfare

The kamikaze suicide pilot was Japan’s most ruthless weapon: On April 4, the Japanese unleashed these well-trained pilots on the Fifth Fleet. Some dove their planes into ships at 500 miles per hour, causing catastrophic damage.

American sailors tried desperately to shoot the kamikaze planes down but were often sitting ducks against enemy pilots with nothing to lose. During the Battle of Okinawa, the Fifth Fleet suffered:

Hacksaw Ridge

The Maeda Escarpment, also known as Hacksaw Ridge, was located atop a 400-foot vertical cliff. The American attack on the ridge began on April 26. It was a brutal battle for both sides.

To defend the escarpment, Japanese troops hunkered down in a network of caves and dugouts. They were determined to hold the ridge, and decimated American platoons until just a few men remained. Much of the fighting was hand-to-hand combat and particularly ruthless. The Americans finally took Hacksaw Ridge on May 6.

All Americans who fought in the Battle of Okinawa were heroic, but one soldier at the escarpment stood out—Corporal Desmond T. Doss. He was an army medic and Seventh-Day Adventist who refused to raise a gun to the enemy.

Still, he remained on the escarpment after his commanding officers ordered a retreat. Surrounded by enemy soldiers, he went alone into the battle fray and rescued 75 of his wounded comrades. His heroic story was brought to life on the big screen in 2016 in the film Hacksaw Ridge—Doss won a Medal of Honor for his bravery.

Suicide or Surrender

Most Japanese troops and Okinawa citizens believed Americans took no prisoners and they’d be killed on the spot if captured. As a result, countless took their own lives. To encourage their surrender, General Simon Bolivar Buckner initiated propaganda warfare and dropped millions of leaflets declaring the war was all but lost for Japan.

About 7,000 Japanese soldiers surrendered, but many chose death by suicide. Some jumped from high hills, others blew themselves up with grenades.

When faced with the reality that further fighting was futile, General Ushijima and his Chief of Staff, General Cho, committed ritual suicide on June 22, effectively ending the Battle of Okinawa.

Death Toll

Both sides suffered staggering losses in the Battle of Okinawa. The Americans bore over 49,000 casualties including 12,520 killed. General Buckner himself was killed in action on June 18, just days before the battle ended.

Japanese losses were even greater—about 110,000 Japanese soldiers lost their lives. It’s estimated between 40,000 and 150,000 Okinawa citizens were also killed. The Battle of Okinawa is now considered one of the deadliest in all of human history.

Who Won the Battle of Okinawa?

Winning the Battle of Okinawa put Allied forces within striking distance of Japan. But wanting to bring the war to a swift end, and knowing over 2 million Japanese troops were awaiting battle-weary American soldiers, President Harry S. Truman chose to drop an atomic bomb on Hiroshima on August 6.

Japan didn’t give in immediately, so Truman ordered the bombing of Nagasaki on August 9. Finally, Japan had had enough. On August, 14, 1945, Emperor Hirohito announced Japan’s surrender, marking the end of World War II.

HISTORY Vault: Pacific. The Lost Evidence

Recounting moments of key battles in the Pacific through the use of photographs and interviews.

Sources

Hellish Prelude at Okinawa. U.S. Naval Institute. Okinawa: The Last Battle. Marine Corps Gazette. Center of Military History, United States Army. Operation Iceberg: The Assault on Okinawa-The Last Battle of WWII (Part 1) April-June 1945. History of War. The Decision to Drop the Bomb. USHistory.org. The Real ‘Hacksaw Ridge’ Soldier Saved 75 Souls Without Ever Carrying A Gun. NPR.

HISTORY.com works with a wide range of writers and editors to create accurate and informative content. All articles are regularly reviewed and updated by the HISTORY.com team. Articles with the “HISTORY.com Editors” byline have been written or edited by the HISTORY.com editors, including Amanda Onion, Missy Sullivan and Matt Mullen.

ENG HACKSAW RIDGE ESSAY.docx. Film Review Essay: “Hacksaw.

Please answer the question along with the explanation Question 32 (1 point) \/ Saved The music for The Seven Samurai contains no elements of Japanese music, as it adopts a Western style completely.

Following Virginia’s poor record with civil rights during the mid-20th century, what was a notable occurrence in the state in the 1990s? A.The nomination of the first black woman to the state

How did Colgate Darden describe Harry Byrd’s view about politics in the Living History Makers interview? A.He viewed politics as a necessary evil B.He enjoyed politics but pursued other hobbies too

Film Review Essay: “Hacksaw Ridge” Jacob Boudreau College of Humanities Social Sciences, Grand Canyon University ENG-105 English Composition 1 Dr. Michael West January 26, 2022

2 Film Review Essay: “Hacksaw Ridge” Would you ever consider going into war only if you didn’t carry a weapon? Hacksaw Ridge. written by Andrew Knight and Robert Schenkkan and directed by Mel Gibson, is based on a true story, following the enlisting of Private Desmond Doss, A Seventh Day Adventist in the battle of Okinawa, Japan. This film highlights one of the bloodiest battles of WWII, and a young Private proving he was a drastic help on the battlefield serving as a medic, even without a weapon. Hacksaw Ridge is filmed and presented by Summit Entertainment and Cross Creek pictures, bringing attention to the gore and heartbreak of WWII. Being released on film to the public towards the end of 2016, Hacksaw ridge won best film editing and sound mixing early in 2017 and continued to win awards as the film became more popular. This film, Hacksaw ridge is effective in meeting the criteria of genre, plot and cinematography because the movie represents its war genre strongly highlighting a main Hero, holds an intriguing plot because he’s an unlikable character at first and becomes the most sought-after during war, and uses incredible sound mixing to recreate the real-life experience. Hacksaw Ridge effectively meets the criteria of genre because it showcases a main Hero in the heart of battle overcoming setbacks to ultimately risk his life for the safety of others. The story being based WWII, allows viewers to get a sense as if they are in the time of war and facing the same setbacks or challenges as the main characters. Main character, Andrew Garfield

Recently submitted questions

The top shell length of male Eastern box turtles is normally distributed with a mean of 120 millimeters and astandard deviation of 15mm. What’s the likelihood a randomly chosen male turtle will have a

Four O’Clock plant flowers exhibit incomplete dominance for color. When a red flower is crossed with a white flower, a pink flower is produced. A white four o’clock flower was crossed with a pink four

According to Rescher, what is the “life-expectancy” factor? After answering this question, say whether the inclusion of this factor amounts to the same thing as “age-based reasoning” and defend your a

Hacksaw Ridge is a red-state movie about a WWII Hero who won’t touch a gun

Mel Gibson is back, with a complicated, bloody story to tell.

Share this story

Share All sharing options for: Hacksaw Ridge is a red-state movie about a WWII Hero who won’t touch a gun

Alissa Wilkinson covers film and culture for Vox. Alissa is a member of the New York Film Critics Circle and the National Society of Film Critics.

Hacksaw Ridge, the first movie Mel Gibson has directed in a decade, is about as Mel Gibson as you can get: grisly, devout, and patriotic, with a deeply complicated core.

Gibson’s wheelhouse, in films from Braveheart and Apocalypto to The Passion of the Christ, is the morally upright, initially reluctant Hero who fights on the side of honor. Usually that fight is a literal battle, the better to unfurl Gibson’s signature torrent of gore. Once, it was a brutal crucifixion.

But the key to all these films is the Gibson Hero, a man of indisputable, uncomplicated virtue, who is at first reticent to engage the enemy. The Gibson Hero is a deeply peaceful man at heart, but when the occasion demands it, he nobly and bravely fights. Hacksaw Ridge is the most clear-cut instance of this template, and one that will play extremely well to the more conservative audiences who also flock to Clint Eastwood movies like American Sniper and Gran Torino.

Given that Hacksaw Ridge is a movie valorizing a Christian man from Virginia who refuses to even touch a gun, that may seem a little surprising. Once you unpack the movie, though, it starts to make sense.

Hacksaw Ridge is genuinely stirring and occasionally corny

Hacksaw Ridge tells the true story of PFC Desmond Doss (Andrew Garfield in full aw-shucks mode), the first conscientious objector to be awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor, given in recognition of his service in the Battle of Okinawa. Doss, whose veteran father (Hugo Weaving) is an abusive alcoholic following his service during World War I, is a Seventh-Day Adventist from the Blue Ridge Mountains. As a young man, he pledges not to touch a gun. But when the Japanese attack Pearl Harbor, he signs up for the Army anyhow, planning to be a medic — with the loving support of his fiancée, Dorothy (Teresa Palmer).

Doss arrives at boot camp to discover that a soldier who won’t handle a gun isn’t very popular, with either his platoon or his sergeant (Vince Vaughn). Everyone assumes he’s a coward, unmanly, unfit to serve. Doss is the target of jabs and beatings from his fellow soldiers, but he sticks to his guns, so to speak, confident in both his convictions and his commitment to his country; eventually he escapes dishonorable discharge and heads off to war as a medic, without a gun.

At this point, Hacksaw Ridge switches from period drama to full-on war film, and Gibson’s favored aesthetic — which is to say, blood and guts — clicks into gear. It’s kind of a jarring shift, because up to the moment battle begins, Hacksaw Ridge is a fairly straight-ahead World War II drama that feels like it was made by a person who’s watched, and memorized, every World War II drama.

The movie veers into dangerously corny territory, especially in the scene in which Doss first meets his fellow soldiers, each of whom is introduced with his nickname and a sly quip that displays his distinguishing characteristic. This feels so formulaic — as does the romance between Desmond and Dorothy — that I suspect it’s a tactic to lull viewers into complacency, the better to throw the upcoming battle scenes into high relief.

But Doss’s real-life heroism is genuinely awe-inspiring, and so by the end you’re rooting for him, and for the film.

Hacksaw Ridge is the movie Unbroken wanted to be

Watching Hacksaw Ridge, I kept thinking of Unbroken, the 2014 war drama about POW Louis Zamperini. That film shares some DNA with Hacksaw Ridge, largely because both of its main characters battle attempts to break their spirits, but also because religion is a key component of their heroes’ stories.

Unbroken fizzled in its final act. It interpreted Zamperini’s strength as merely the ability to outlast his enemies’ endurance, and expected viewers to find that inspirational. It is, to a point. But the real Zamperini emerged embittered and broken from his time in a prison camp, and it wasn’t until he experienced a religious conversion that he realized that the way forward was to love his enemies. He returned to Japan and forgave his captors in person. That’s the story the book tells, but the film reduces the final act to a few title cards, and thereby loses its arc.

Hacksaw Ridge attempts, and mostly succeeds, to tap into the same audience and thematic material as Unbroken. Clearly targeted at viewers who prize God and country, it gives us a brave and good man — Doss has no flaws, no moments of weakness past his conversion moment — whose insistence on following the dictates of his conscience is his strength, and who derives courage from his faith. Slowly, the people around him come to respect and depend on his faith, even if they don’t share it.

And as I said, it mostly succeeds at its goals. Only a stone-hearted robot could be completely unmoved by Hacksaw Ridge, which tugs relentlessly on your heartstrings at every opportunity.

This is both its strength and its weakness. The score swells a bit too earnestly and the images are shimmery and idealized, a heightened reality that seems like it may belong more to a fairy tale or a fantasy epic than a story about a war in which a lot of people died. (And in contrast to a director like Eastwood, who paired Flags of our Fathers with Letters from Iwo Jima, Gibson isn’t very interested in humanizing the enemy. There’s maybe one moment of recognition that the Japanese enemy soldiers are people with families as well.)

But even if Hacksaw Ridge leaves your heartstrings a little frayed, a man who risks his life to save so many people on the battlefield is undeniably an inspirational figure. In the end, it’s heartening that such men exist, whether or not you share his convictions.

Hacksaw Ridge isn’t about pacifism. It’s about conscience.

The most notable thing about Hacksaw Ridge, though, is Doss’s insistence on nonviolence — not precisely what you expect from a movie that’s obviously intended for the same audience as American Sniper. Doss recoils from even touching a gun. He will not take a life; being a Seventh-Day Adventist, he is even a vegetarian.

At first this seems like a rather revolutionary stance for such a film: A heroic war movie where the Hero is against guns, even in self-defense? When that plot point first emerges, it’s startling. But it gets complicated pretty fast.

Lego WW2 Battle of Okinawa (Hacksaw Ridge) / Битва за Окинаву (Хэксо Ридж) / Pacific war

For instance, Doss is convinced that his faith is opposed to killing, even on the battlefield. And yet you can’t exactly call him a pacifist (though maybe a pacificist). In many scenes, he allows his fellow soldiers to cover him by returning gunfire. Similarly, in one scene near the end, he doesn’t technically activate a grenade, but he causes it to explode near his enemies — a scene the movie doesn’t interpret as violence, though it destroys life.

But in general, Doss’s stance of personal nonviolence, even if it’s in service of a war, is one of the character’s surprising strengths: He isn’t insisting that everyone conform to his religious standards, just that he must uphold his convictions while pitching in. Some religious pacifists have tended to see their resistance to war as a resistance to the power structures of the state, which conflict with God’s authority. But Doss loves America, and will do what he can to help the cause.

So while at first it seems like Hacksaw Ridge is an anti-gun movie for the Second Amendment-revering crowd, that’s a shallow interpretation. For one, Gibson hasn’t suddenly turned against violence. This is a bloody movie with no sense of scale; it’s not enough that we see one guy’s legs get blown off, but we must see him get dragged across the ground, bloody stumps behind, and then see the same thing repeated four or five times. Pieces of bodies, heads exploding from bullets, guts all over the place — it’s all here, shot with reverence rather than disgust.

Violence, in Gibson’s view, is a glorious aesthetic choice, and Hacksaw Ridge’s violent imagery goes so far and goes on so long as to be completely numbing. It’s the opposite of the effect Gibson presumably intended, making viewers feel the brutality of war. In cases like this, sparseness can be a virtue.

In any case, it’s more accurate to view Hacksaw Ridge as a pro-conscience movie than an anti-gun movie. Its implicit argument is that a free country must make room for principled objectors. Doss is effective precisely because he’s as courageous as any soldier, but he channels his extraordinary courage into his work of saving the wounded. The movie suggests that without him there — without someone who objects to violence in the midst of those who are there to kill — many more soldiers’ lives would have been lost. And so the platoon is in fact fortunate to have a man without a gun among them; his conscience restrains him in some ways and empowers him in others.

This is the basis of some conservatives’ position on matters of religious freedom — that it is to society’s benefit to allow for some to object in order to provide balance and restraint in situations with moral and ethical weight.

Obviously that’s a deeply complicated matter. But whether or not you personally think that position holds weight, it’s certainly reflected in Doss’s story.

So if and when Hacksaw Ridge does gangbusters business at the red-state box office, it would be wrong to mistake that for a spasm of anti-gun sentiment. The movie mixes a Hollywood-style celebration of heroism in a popular setting with a matter of very contemporary importance — and whatever its cinematic faults, it’s hard to emerge from the theater unmoved.

At Vox, we believe that everyone deserves access to information that helps them understand and shape the world they live in. That’s why we keep our work free. Support our mission and help keep Vox free for all by making a financial contribution to Vox today.