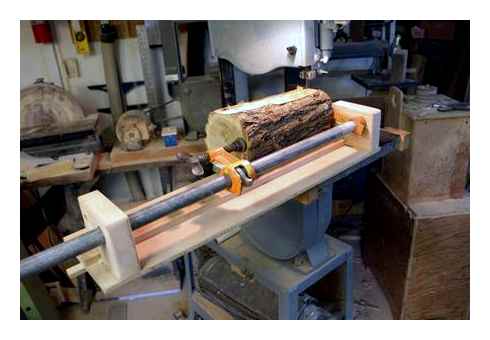

Cutting a Log on a Band Saw. Band saw log sled

Cutting a Log on a Band Saw

I recently created a project for my mother and father that involved turning a fallen tree branch (struck by lightning) into a Cheese Tray and Coaster set. This spawned a lot of questions from my audience about what is required to actually turn a log into usable material for a wood shop project. It’s not as simple as cutting the tree down or branch off and cutting it up. Additional steps must be taken for the wood to turn out usable and to make sure it is done safely!

Trust me when I say there are a lot of varying opinions on what is the right way (or wrong way) to mill logs into dimensional lumber. In this article I hope to address some of those ideas and concerns and make you a little more informed so that you can decide what’s the right way for the material and the tools that you have available in your shop.

Making Dimensional Lumber from a Log or Branch

The first thing you need of course, is a log or tree branch. If the tree is still alive and growing, or has just recently been fell, this wood will most certainly still be green and wet. It will not be usable in this state. If it’s been laying in the yard or forest (or Grandpa’s back 40) for years it might be too rotted and cracked to be usable. Wood needs to go from wet to dry before you can use it and there are multiple ways to get it to this dry state In this article I am not going to discuss the correct moisture content for dried lumber. It varies from climate to climate and wood type to wood type. There’s an extensive article at Wikipedia on just this topic alone.

Dry the Wood Before Use

Before you use your wood on your project it needs to be dry. The most common way to do this is to simply let it sit for a long period of time. In the case of my Cheese Tray and Coasters project I let that log dry for approximately 14 months. A larger log would have take even longer. To make the dry time go faster you can use a chainsaw mill and slice the logs in large planks and store them with slats between them to keep air flowing between each individual plank. Matt Cremona has a great set of YouTube videos on this process.

You can also dry wood faster using a kiln, your home oven, or even a microwave. However, those topics are complicated and beyond the scope of this article. Regardless of how you decide to dry your wood, it remains the most important step in the process. Failure to dry the wood is going to result in major warping. splitting and cracking, failure of glue joints, and of course the gumming up of your saws and tools with sap and water.

I suggest purchasing a moisture meter from Amazon or your local woodworking store like Rockler.

Create a Band Saw Milling Jig

To safely mill your log into dimensional lumber you’re going to need a milling jig. There are many variations of these jigs, but the simplest one is simply two sections of plywood connected together to form a 90 degree angle. A milling jig then either clamps or screws to the log. This will keep the log from rolling, rocking, or otherwise moving as it passes through the saw. Just as importantly it provides two flat surfaces to run along the the table and the fence of your Band saw (or even table saw). This will allow you create two flat sides on the log. Plywood is a great choice because it has plies of alternating grains is most likely to stay flat and warp free.

Slicing the Log into Lumber

Once you have two sides cut, forming a 90 degree angle you can remove the jig and begin to slice your material into usable lumber. Depending on the thickness of the log you do this process on your Band saw, or move to your table saw. The Band saw will slice larger logs and leave a smaller kerf, while the table saw will leave a smoother finish.

Storing the Lumber

If you’re not planning on using the lumber immediately, it’s a good idea to store it laying flat and to number it. This will allow you to take advantage of the book matching pieces if you get the opportunity to join the sections for a larger project.

Harvesting Backyard Exotics: There’s No Place Like Home For A Bonanza Of Beautiful Woods

This article is from Issue 61 of Woodcraft Magazine.

There’s no place like home for a bonanza of beautiful woods.

Imagine walking into a lumber dealer’s show room and having first choice of all the best material–wide slabs of walnut, quartersawn sycamore, and cherry planks milled to exactly the right thickness for your next project, all with matching grain and color. Just down the aisle you encounter stacks of beautiful boards of exotic native species you’ve never seen before. Imagine all of this for less than 75¢ per board foot!

If your property or neighborhood has a stand of trees, you may be wood-rich … maybe super rich.

Oftentimes (depending on where you live), urban, suburban, and acreage yard trees include the usual oak, maple, and ash, as well as less common gems–what I call “backyard exotics.” (See “Less Common Gems,” above) For those of you who have a variety of trees growing on your land, you may have all the woodworking woods you’ll ever need. All you lack is the equipment and know-how to transform the resource into usable stock. That’s why teaming up with a sawyer (as T. J. Palmer of Joplin, Missouri, did when he hired me to mill logs he had cut from his woodlot) makes sense and is the safest way to go.

By working with a sawyer, you can determine how you want to slice the wood for best effect. You may want to quartersaw a white oak log to mine impressive ray-fleck figure or slab the crotch wood in a walnut for a stunning accent table. Perhaps granddad planted a tree a half century ago, and you want to transform its wood into an heirloom bowl or furniture piece in his memory. The reasons abound for harvesting homegrown woods.

Less Common Gems

Here are just some of the woods I harvest around the Joplin, Missouri, area. The samples include: 1. catalpa, 2. sassafras, 3. sweetgum, 4. spalted sycamore, 5. mimosa 6. Osage orange, 7. quartersawn sycamore, 8. hickory, 9. honey locust, 10. walnut, 11. black oak, and 12. mulberry.

Identifying suitable trees

Start by finding a suitable candidate for harvesting, keeping these pointers in mind:

- Size: Most portable sawmills can handle logs between 10″ and 30″ in diameter, but a few will cut logs outside that range. The ideal log length runs between 8’4″ and 12’4″.

- Form: Straight logs give the best yield if you are looking for straight boards. Curved logs can be cut lengthwise to produce curved slabs with natural edges that make interesting benches, bar tops, and accent tables. Crotches can yield spectacular feathered grain.

- Species and identification: Most sawyers know the local species, but all bets are off with ornamental trees, which may come from half-way around the world. Rely on the Audobon Society Field Guide to North American Trees as a reference for identifying native species.

- What to avoid: Trees that branch out low make poor saw logs. If the tree has been dead, it may have rot or be hollow. Consider the tree’s origin (urban vs. forest.) Urban trees are notorious for containing metal. Scan suspect logs with a metal detector. They could have fence wire, nails, or even a steel post embedded. Finally, don’t mill branches, even if they’re big and straight. They contain stress and may warp beyond use.

Brush on a thick coat of latex paint or Anchorseal 2 (Woodcraft #150809, 24.50/gallon) to seal the ends of logs and prevent end-grain checking.

Finding trees

Make sure you really want to remove the tree for woodworking stock. I would never recommend an urban tree be cut down just to make something out of it. Still, if you have a dead or dying tree, or one that otherwise needs removal, why not make the most of it?

Beyond your property line, keep an eye open for trees marked for removal. Knock on a neighbor’s door to ask about a tree. Sweeten the deal by offering the owner a bowl or other piece made from the wood. I’ve offered split firewood to those who burn wood in their fireplace. Because you’ll have to haul the logs home, don’t bite off more than you can chew.

Felling trees

Leave the hazardous business of felling a tree to a bonded and insured tree service with the right equipment to do the job safely. Your portable sawmill guy may be qualified. In any case, avoid doing it yourself with a chainsaw. There are too many risks. Tree services can be expensive, but they earn their pay! Tell them what you want done. Once the tree is cut into usable logs, seal the ends (Photo A).

Finding a sawmill

There are thousands of portable and custom sawmills across the country. Do a web search for those in your area. The state forest products association, Department of Conservation, and SawmillFinder.com are good resources.

Arranging for milling

When you talk to a sawyer, describe the size and number of logs accurately. Be up front about them coming from a yard. Many sawmills will refuse to cut yard trees because of the high probability of hitting nails and other embedded metal. Others take it in stride, but will expect you to pay for a new blade (around 30 for a bandsaw blade) if they strike metal.

Keep the logs clean. Dragging them on the ground crams dirt in the bark, which is hard on bandsaw blades. Lift the logs and carry them, if possible. Even lifting one end while moving them helps. It’s easier on your yard too.

Most sawyers charge from 30¢ to 50¢ per board foot, which works well for straight logs. Charging by the hour is the most reasonable way to deal with specialty cuts such as crotches, short pieces, and quartersawing, since they require more handling. The average rate is around 60/hour. Other charges may include transportation and setup fees if the sawyer brings the mill to you. Still, you should beat the 75¢ per board foot cited earlier.

If the customer is willing, I’ll put him or her to work off-bearing the boards. I generally enjoy having the customer work with me, especially when cutting unusual wood, because we can discuss the various possibilities. Some sawmill operators have strict rules about what a customer can do because of liability issues.

To get the most out of your logs, know ahead of time what you want as an end product. The sawyer will cut accordingly, accounting for shrinkage as the wood dries and the loss of wood from planing. If you have a specific project in mind, make a cut list and let the sawyer decide the most efficient way to mill what you need.

Sawmill Options

Several choices lay before you when harvesting the bounty of backyard woods:

Use a chainsaw mill to slice up a few logs or logs in heavily wooded areas that are hard to get to with a portable bandsaw mill.

Hauling your logs to the sawmill

If you just have a few logs and a way to move them, you can save some money by bringing them to the mill. I schedule a log drop-off so that the customer can deliver the logs and return home with the boards all in one trip.

Just loading the log on a trailer can be a wrestling match, involving winches, ramps, and other equipment. And you’ll need straps. Heavy ratchet straps used by truckers are great. Hauling logs and lumber puts a serious responsibility on you. Make sure your vehicle has adequate towing capacity and that the trailer is rated for the weight of your logs. On the return trip, be sure the load is securely strapped down and that the straps put pressure evenly across the boards.

Have a portable mill come to you

If you don’t have a safe way to haul logs and lumber, find someone with a portable sawmill to come to you, as shown on page 30. To help the sawyer’s job go smoothly, pile up or line up the logs on level ground to give him plenty of area to work in–at least a 30′ square. Provide logs for blocking and 1 × 1″ stickers to air-dry the sawn boards. Stage the logs so that the sawyer cuts the best ones first. By day’s end, you may not get to all of them.

Do-it-yourself chainsaw mill

If you decide to mill your own logs, consider a chainsaw mill (Photo B).

The minimum size saw recommended is 70 cubic centimeters (c.c.), but most mills run saws over 100 c.c. The bar needs to be longer than the widest diameter you will cut, and you need a special ripping chain. Add to this the safety gear (chaps, helmet, and steel-toe boots), and you have a significant investment (about 1,700). Many people use chainsaw mills to cut logs where they find them, which lets them move the log one board at a time.

Run the log-bearing sled along the saw’s fence (or a clamped-on makeshift fence) for resawing slabs or cutting turning squares.

Working with a shop bandsaw

Bandsaws of 1.5 HP or more can be used for milling small logs. I recommend a 1″-wide resaw blade with 3 teeth per inch, though 1.5 to 2 teeth per inch would work well for more powerful saws. The key is to use a sharp blade and to feed the log through at a steady pace. One way is to pass a manageable log over the jointer to get a good flat side, and then use the fence on the bandsaw to cut your boards. If you mill regularly, make a right-angle sled (Photo C).

Secure the log with screws through the sled’s fence and into the log’s waste area.

Wood Grain Key

Flatsawn boards2. Boards with pith (tend to have cracks and warp more)3. Quartersawn boards (most stable and can have figure)4. Riftsawn boards (with growth rings from 45° to 75°)5. Slab or waste wood (for rustic projects or firewood)

Cutting Key:

A. Flatsawing is where a log is squared into a cant, and then cut into straight-edged, flatsawn boards with arcing end grain. (Most common and efficient method of cutting.)B. Flitch-cutting slices boards in sequence from top to bottom. It yields the widest boards,keeps the natural edges, and gets the most out of a log. Board edges may require trimming later.C. Quartering, or quartersawing, is where a log is cut into quarter sections and then the quarters are sliced, yielding more quartersawn vertical-grain boards. initial handling at the saw is required.D. Quartering and turning means a quartered log is turned 90° after each cut to yield the most quartersawn lumber. A lot of work is required by the sawyer resulting in added costs.

I like to spread water on freshly cut crotch slabs to reveal the beauty of the book-matched pieces or other figured woods.

Cutting Options

Wood can be cut so as to bring out the best grain and physical properties. The sawyer can figure out ways to maximize the cuts you want. As shown in Figure 1, here are your cutting and grain options:

- Plainsawing cuts the wood tangential to the growth rings. This common cut yields V-grain patterns in most species. It can result in cupping, so you may want to cut wide boards thicker. Also consider ripping them down the center before planing, and then jointing and edge-gluing them back together. The cupping makes it important to kiln-dry the wood or otherwise bring it to a moisture content of about 7% for use indoors.

- Quartersawing cuts the wood perpendicular to the growth rings. This “vertical grain” stock proves more stable, being less prone to cupping. For most species, quartersawn wood has a special shimmering quality, but in some species, such as oak and sycamore, the wood rays yield beautiful flecked or quilted patterns.

- Flitch-cutting means sawing the boards while leaving the natural edges. This wood can be challenging to work with, since you do not have a straight edge for reference, but it is a favorite of rustic woodworkers and is becoming more popular in custom furniture. One advantage is that pieces can be book-matched to give a symmetrical mirror-image grain pattern that creates stunning tabletops. Flitch-cutting is especially useful for crotch wood, as shown in Photo C, and for curved logs.

Taking Care of Your Lumber

As soon as you cut a log, seal it as covered earlier. It’s best to mill the log as soon as possible after the tree has been felled. This is critical for species, such as hickory and sycamore, that decay quickly. Oak–especially white oak–is more durable. I have milled walnut that has been on the ground for at least eight years. The sapwood has rotted off, but the heartwood is still solid. If you can’t mill the logs within a few weeks, store them off the ground to avoid decay.

Air-Drying

Once you mill the wood, air-dry it. In hot, humid environments, fungus will be noticeable within 24 hours. The ideal location for air-drying wood is a level area out of direct sunlight with good air circulation. If possible, start with a layer of plastic on the ground to keep ground moisture from coming up through the stack. Then, place 4′-long 6×6 timbers, distributed evenly on 20″ centers for 1″-thick boards (Photo D). Place a 3⁄4″-1″ × 1″ × 4′ “sticker” (spacer) on top of each of the timbers. The 20″ spacing is required to keep the boards from sagging. Now, place your first layer of boards. They should be of the same thickness so that the stickers will lie flat to support the next layer. The 3⁄4″ or greater gap between the boards should guarantee good air circulation. When the layer is complete, place another set of stickers directly above the ones that support the layer below to distribute the weight evenly. If possible, put a tarp, metal roofing, or other material over the stack to keep moisture off. Weigh it down with cement blocks or water barrels to reduce warping. Now comes the hard part–waiting. The rule of thumb is one year for each inch of thickness, though this varies with climate and species. Note that this conventional stack disregards the cutting order of the boards.

To maintain the cutting order, stack flitchsawn cuts using the “European” method (Photo E). This reconstructs the log with stickers between the boards for air circulation. The advantage is that it keeps the log together, making it easier to book-match flitches. This also makes it possible to mill to different thicknesses, since each flitch makes its own layer. The slab on top provides natural protection from rain. Use a ratchet strap between each column of stickers, and tighten it down once a week as the wood shrinks.

Kiln-Drying

The best way to keep track of the wood moisture content is to use a pin-type moisture meter, available for under 50. Once the wood drops to 12%, it will not air-dry further in most locations. For the moisture content to match the indoor humidity of your home, bring the wood indoors and use a fan for air circulation, build a small kiln, or send it out to be kiln-dried at 30¢ to 50¢ a board foot.

How to Saw Lumber with a Bandsaw Mill (7 Steps Solution)

Dealing with lumbers is not an easy chore for any carpenter. To turn those bulky lumbar into usable boards, they go through a number of complicated cutting, sizing and finishes chores.

So, you might pick up a way to cut them with a bandsaw mill. So, it’s pretty obvious to come up with a question of- how to saw lumber with a bandsaw mill?

And how would be the quality of the cuts? Will this process ruin the woodwork?

Well, we’ve gone to the roots of this topic and we’ve researched it thoroughly. And we believe that if you follow the process perfectly, then there will be no quality issue.

So, it’s super important to follow the right process.

Basics of Sawing Lumber with A Bandsaw Mill

Carpenters and woodworkers usually don’t have the practice to saw lumber of logs with a bandsaw. But for your utter surprise, it’s very possible to do so and that’s what we will talk about in today’s post. But before that, here are some basics-

What Size of Lumber Should You Cut with A Bandsaw?

It’s quite important information to know what lumber sizes are able to be cut with a bandsaw. Usually, lumber and logs that lie within a diameter range of 16 to 18 inches are able to be cut under a bandsaw mill. The length should be around 2 feet.

Steps of Cutting Lumber with A Bandsaw

This is the core of the article for which you’ve been through the entire post. At this stage, we will take you through a 7 steps guide on how to cut lumber with a bandsaw mill.

Before starting, let’s assume that you’ve managed to cut the tree branch with a thickness of 16 to 18 inches, and a length of about 2 feet, and a bandsaw mill itself.

If done, let’s proceed with the steps of how to saw logs with a bandsaw mill –

Step 1: Mark the Miter Bar Locations

At first, you have to make the sled, which is a pretty easy task. It is a piece of ¾ inches of MDF which is 10 inches wide and 2 feet long. Now, measure the distance from the blade to the miter track. And afterward, it’s transferred into MDF.

Once done, lay an 18 inches long miter bar on the line and mark the location of the hole from the miter bar. It’s quite an effective bandsaw cutting technique.

Step 2: Attach the Miter Bar

Once done with step 1, you need to attach the miter bar to the flat-headed machine screws. Before that, you need to drill the countersunk holes into the MDF.

You have to prevent log sliding on the surface of the sled. In order to do that, a proper bandsaw operating procedure is mandatory. You need to cut a piece of drawer liner and use an adhesive spray to keep the log in place.

Step 3: Making the First Cut

Once done with steps 1 and 2 of how to saw lumber with a bandsaw, it’s time to make the first cut on your lumber. While going through the process, you need to make sure that any kind of log rocking doesn’t take place. In order to do that, you might need a wooden shim anyway.

Have a prediction of what you need to cut off in order to leave it with a flat surface. Eventually, you will find that it’s quite easy to pull the log gently and cut off the last few inches of the log.

It will eventually help your lumber to balance its weight. Based on the wood type, you can make other types of cuts as well.

Step 4: Making the Second Cut

After the 1st cut, it’s time to make the second cut on the lumber. It would be quite easier if you have made the first cut perfectly. The reason behind this is the bottom surface is now flat.

In the second cut, you have to take off a small amount of wood in order to leave it with a smooth surface. Don’t waste too much wooden portion of the lumber.

However, if you’ve to do resawing with a bandsaw. this step should be repeated several times.

Step 5: Cut the Boards

The reason why you are learning steps of cutting logs with a bandsaw mill is maybe, you want to make boards out of it. If so, you have to do the task of making boards at this step.

At first, decide the thickness of the boards that you want to cut. Usually, we would go with a board that is 1 inch in thickness. Once the first two cuts are done, take off the sleds and set up the entire fence of the bandsaw.

To get the most number of boards out of the lumber, you might alter the direction and face of the lumber after cutting each 1-inch board. The side that was facing down at the previous cut, should now face the fence at the next cut.

Step 6: Dry off the Boards

The boards that you have sources from the lumber, has to be taken through a processing phase to make them usable. It all starts with drying them up to get out the extra moisture from there.

To dry them up naturally, unstack them up, and expose the surfaces of them to open air. Don’t put them in a place like direct sunlight or heat. This will eventually, build cracks on the board.

Step 7: Smoothen and Surface the Boards

Once dried up, the boards are supposed to be surfaces and smoothened up. This particular task is done in many ways by many carpenters. We get to use a moisture meter to make sure that the board is with perfect moisture.

Once done, rip off the outer edge of the boards, and run them through a series of planer and jointer. Make enough planning that no unfinished surface is not there.

Bandsaw Sawing Techniques

Our described method was just one method of sawing with a bandsaw mill. We have 5 available methods of doing this.

And each of the techniques has a different name. Here’s a list of all the methods of using a bandsaw to cut lumbers-

- Live sawing or Slab Sawing (The technique described up there)

- Cant Sawing

- Grade sawing

- Plain Sawing

- Quarter sawing

Milling Wood Using a Bandsaw. Logs to Live Edge Lumber

Each of the methods has its own perks and cons. So, it’s important to choose the right technique in the right situation.

Bottom Line

That was the guide on how to saw lumber with a bandsaw mill. Hopefully, the steps have been easily explained to you.

If you still have any questions left, leave that in the comment section and we’ll come up with tips for cutting with a bandsaw.

Make a Bandsaw Sled to cut Log Slices

Words: Damion Fauser Photos: Donovan Knowles

The versatility of the bandsaw basically comes down to its anatomy. With most woodworking machines an element of rotational or lateral vectors are applied at the intersection of the blade and the stock. On a tablesaw this can contribute to kickback and it’s also why we need to always mill stock on the jointer from the right to the left.

On a bandsaw the vectors applied at the cut are lineal, and the direction of force applied is downward onto the table, rather than laterally across. This makes the bandsaw a far friendlier machine to use and that’s why I do most of my ripping on it.

Setting a zero-clearance base in place.

Damage control

With a downwards cut the teeth exit stock at the base, so this is where any chipping or tear-out will occur. On finer cuts, or to minimise damage, add a zero-clearance base to the saw table. Simply take a small sheet of masonite, set the saw fence to the desired setting and run the masonite partially through at that setting (photo 1). Stop the saw and clamp the masonite in position to give a clean and slick surface and protect against tear-out.

Get the best tooling

Remember it’s not the machine that makes the cut – it merely drives the blade. To get the best performance out of your bandsaw invest in the best tooling you afford. I use BiMetal blades for general cutting and carbide-tipped blades for times where I need to maximise performance and minimise waste.

Sawing boards from a log

Log-cutting cradle with a log screwed in place.

Knowing how to yield boards from a log or branch can help maximise resources. Here the bandsaw excels, and the average mid-sized 14″ or 16″ machine will easily handle a log in the order of 1000mm long and up to 150mm thick. For larger logs you need outfeed supports or an assistant.

A jig will help you traverse the round log in a straight line past your blade. A simple right-angle section can work as a cradle with the outside face running against the fence.

The log is fixed to the inside of the cradle with countersunk screws from the outside of the jig, both the vertical side and from underneath to give maximum support. The screws will go into bark and sapwood so the holes will be sawn off. Always be aware of the path of blade when positioning the screws so you don’t damage the blade (photo 2). Set the fence so the blade will skim off the outside edge of the log, to give an initial flat surface.

Making the second cut to yield the second flat surface.

Once the first two flat faces are cut you can just run the log on your saw without the cradle.

Detach the log, rotate it 90° to now register the flat face into the cradle for better support and then take another pass to yield a second flat surface perpendicular to the first (photo 3). Now you have a piece of wood that can be safely jointed and registered at the table and fence of your saw for sawing boards (photo 4). Store your boards for drying and check their moisture content before use.

Cutting narrow stock into veneers

Making the most of a special piece of wood by resawing it into veneers makes sense. Shop-made resaw fences will allow you to do tall resaws. Use MDF to make simple jigs supported by 45° brackets glued and screwed in place. Take a small chamfer off the bottom of the vertical face of the fence to provide clearance for any errant dust during the cut.

The resaw fence is clamped in place directly to the table. The distance from the blade determines the thickness of your resawn components. If your saw is already adjusted for drift, use a square to set the fence square to the front edge of the table. Otherwise, determine your drift angle and set the fence using a bevel gauge set to that angle (photo 5).

When determining veneer thickness and the number of pieces don’t forget to take account of the kerf (blade) thickness. I generally saw veneers 2.5–3mm thick and then dress them down to around 2mm.

Remember these are ripping cuts, but you are asking the machine and the blade to remove a lot of material, so slow the feed rate down to give the gullets a chance to remove the waste (photo 6). You may need to redress the sawn face so it registers cleanly against the fence for the next pass.

If you plan on arranging your veneers into a decorative pattern, ensure you mark the edge of the stock with a cabinetmakers triangle prior to sawing so that you can always rearrange them into their original orientation when experimenting with your patterns.

Cutting narrow stock into strips

Narrow strips are useful for edge- bandings, string inlays, splines and more. This is also just a ripping cut, but a very thin one so you might want to use a blade with a finer pitch. Start by using the techniques from resawing veneers to take wide, thin strips. Set a zero-clearance base down on your table at your desired fence setting.

Because the guides may interfere with lowering the post down, either use a supplementary fence made from a piece of plywood, or if your machine allows, rotate the fence extrusion 90° (photo 7). Redressing the reference edge each time ensures at least three dressed faces, meaning strips can be rotated for optimal grain orientation in a project without further work.

Cutting wedges

To make a jig for cutting wedges, first mark for a 5° notch.

Wedges are one of the most useful workshop accessories, though I mainly cut small wedges for wedging through tenons. I generally use a 5° angle for my wedges. Draw this in from the edge of a piece of dressed wood and then bring it back up to the edge so the resulting drawn angle is 90° (photo 8). Bandsaw the long section, trim off the short one, then clean up the two cut surfaces with a chisel (photo 9).

Using a chisel to clean the saw marks from the bandsawn notch.

Set the fence so the blade runs just along the outside edge of your jig. Run and clamp a zero-clearance base in place to stop the cut wedges from disappearing down the throat plate and getting caught in the lower guides.

Push the stock all the way past the blade to prevent the wedge being caught by the blade.

Now take your wedge stock, locate it into your 5° notch and run the pass through to the rear of the blade (photo 10). Your wedge will drop onto the table when you take away the stock and will have a nice clean knife-edge to it (photo 11).

Cut wedge showing the knife edge that is possible.

Take a wedge off the other corner, then take two more wedges from the other end.

Flip the stock to take a wedge off the other corner at that end and then rotate the stock to take two more wedges from the other end (photo 12). Whilst you have this setup in place, run a quantity of wedges to store for future use.

Cutting tenons

The bandsaw excels at this task because the cheek cuts are square and flat. It is easy to set a stop block to stop the cut at the shoulder and if doing twin tenons, it is also easy to use nibbling cuts to remove the waste in between the two tenons.

Lay out your tenons (photo 13) and then set the fence to cut the inside cheek, ensuring you keep the blade in the waste.

Set a stop block on the fence to hold the cut at the shoulder.

Mark the shoulder, line it up against the front edge of your teeth and use this to visually set and clamp a stop block on the fence (photo 14).

Run the first outside cheek and rotate the stock 180° and run the opposite cheek (photo 15). Leaving the fence in place, place your stock against the blade as if it was going to cut the inside cheek. Your stock will be offset away from the fence – mill a piece of wood to that thickness and then you can use that to shim your workpiece away from the fence and make the two alternate cheek cuts (photo 16).

Using a shim to cut the inside cheeks.

With this shim technique, you only need the one fence setting to make four cheek cuts, which will save you enormous time. Careful planning will allow you to use this fence setting to also remove the sub-cheeks to form the shoulder all around the tenons (photo 17). To remove the waste in between the two cheeks, push the stock into the blade to take nibbling cuts – the stop block will prevent you from going below the shoulder line.

For the shoulder cuts use a crosscut sled on the tablesaw or do them by hand as it is important to have clean and crisp shoulders. In photo 18 you’ll see that I’ve just buzzed them off at the bandsaw for the purposes of this article to show the final result.

Trimming splines

Mitre splines are a great way to reinforce and decorate small mitre joinery. Trimming the excess spline material away can be risky and time- consuming, but a bandsaw jig can counter that.

Spline trimming jig showing notch to house the blade.

Take two pieces of MDF and fix them together with the top layer offset and parallel to the bottom layer. Cut a small notch away from the edge of the top layer – this is where the bandsaw blade will travel during operation. Position the jig so the edge is square to the front of the saw table and the notch houses the sawblade and then clamp it in place. Now you can simply run your project against the edge of your jig and the saw will remove the excess spline material quickly and easily (photos 19, 20).

And dovetails too!

Yes, the bandsaw can even cut dovetails. In my experience, one of the most common causes of poor dovetails is the inability of the woodworker to make repetitive and accurate tail and pin cuts that are square. The bandsaw ensures each and every one of these cuts is perfectly square.

In issue 94, I showed how to make stock that tapers from edge to edge using the planer/thicknesser. Use this technique to machine some stock with an angle suitable for dovetailing (9.46° for 1:6, and 7.13° for 1:8) and then glue a small cleat on the top along the low edge. Layout your pin spacings on the end of your pin boards (highlighted with a marker pen for the photos), register it against the cleat and use this to set the fence to make the cut on one face of the first pin.

Use a series of shims to progressively space the jig away from the fence to make the first cut on successive pins. Once you’ve made the first cut on the pins, rotate your jig end-for-end and repeat the process to make the second cut on each pin (photo 21).

Tail-cutting jig with registration stop for symmetry.

Take a bevel gauge and set it for the angle of your pin-cutting jig. Now take this angle and use it to mark out a tapered long edge on another piece of wood to act as the guide for cutting the tails (photo 22). Glue a small offcut to one end to act as a cleat for registering your tailboards.

Bandsawn dovetails, straight off the saw.

Set the fence to make the first cut of the first tail. Because this jig is symmetrical, you can simply flip your tailboard and make the first cut of the opposite tail. Now, use a series of shims to progressively space your jig away from the fence to make the successive cuts. Remove the socket waste as you normally would and, if you’ve been careful in your setups, you’ll have fantastic dovetails straight off the sawblade (photo 23). This technique takes some time and diligence to setup accurately so it’s best kept for a job with a lot of cutting to do.

Template trimming

The bandsaw can be used to remove waste from template components to within a consistently fine distance without risk of cutting below the line, leaving components that are ready to be buzzed off in your templating jig.

You’ll need to make a simple jig that consists of one base platen and a second birds-mouth component fixed perpendicular to the first. The birds-mouth notch is where the sawblade will run and the template runs against the mouth of the birds-mouth (photo 24).

Fix your template to the stock with double-sided tape and start the cut, carefully registering and running the template against the end of the birds-mouth. Careful setup will leave you with the perfectly consistent amount of material to remove at the router table or shaper.

Understanding how the bandsaw works is the key to exploring its versatility. Grab some scraps, make some simple jigs and have a go. I’m sure you’ll enjoy the process and improve your woodworking.

First published in Australian Wood Review, issue 98. This short video shows a few of the techniques above.

Damion Fauser is a furniture designer/maker who lives in Brisbane. He teaches woodwork from his Brisbane workshop, see damionfauser.com.au